Silence is not absence—it is a higher form of presence. In the work of Jaume Plensa, every material—whether iron, alabaster, light, or word—becomes a way to touch the ineffable. From his studio in Barcelona, the artist has shaped a sculptural language where the body is both a boundary and a portal, where spirituality does not impose itself but seeps through, like air between the letters of a translucent sculpture.

With over four decades of artistic practice and public installations on five continents, Plensa has transformed public space into a realm of intimacy. Crown Fountain in Chicago, Behind the Walls in New York, Water’s Soul in New Jersey—his works are not monuments to the ego, but collective mirrors. “Sculpture is the intimate dialogue between the human being and their heart,” he says. And that dialogue feels more urgent than ever.

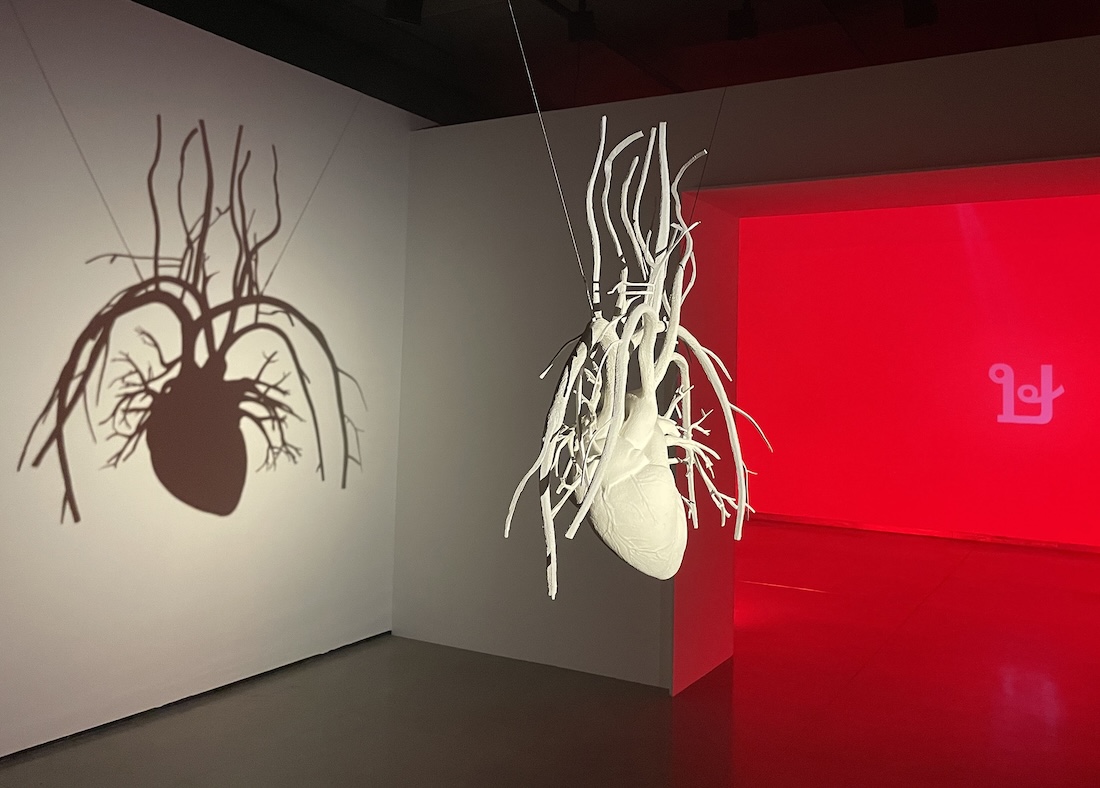

Between October 2024 and September 2025, Materia Interior—his major retrospective at Espacio Fundación Telefónica in Madrid—condensed thirty years of essential questions: What does it mean to be moved in a world that has become blind to pain? Can art still offer refuge, memory, shared breath? Through fifteen key pieces, the exhibition revealed a constant core: the human being as center, as map, as mystery. “There has been no evolution, but rather expansion: concentric circles around the human being,” Plensa reflects.

An artist, visual poet, and creator of quiet gestures that cross languages and cultures, Plensa has also worked in theater and opera—most recently directing and designing Macbeth by Verdi at the Gran Teatre del Liceu in 2023. His work doesn’t seek to impose; it seeks to resonate. “Art should be that place you can always return to: the hand of the person you love, the smell of bread, the rain, the tears…”

In this conversation with Art Summit Magazine, Jaume Plensa speaks of language as living matter, of intuition as a compass, of sculpture as a threshold between what we see and what remains unseen. And of how, sometimes, a single comma can shift the entire cosmos.

An Interview with Jaume Plensa

By Carol Real

What part of you has remained intact since you first felt that art was the only possible language?

I believe in the will to grow first and let the work be a consequence of my life. To maintain doubt, questioning, and inquiry as the foundation of the work.

If silence has always been your ally, how do you protect yourself from overexposure, digital noise, and immediacy?

Sculpture is a great ally of silence, given its inherent impossibility to describe and narrate. It is, without a doubt, the intimate dialogue between the human being and their heart.

What does it mean to you to sculpt words, to give them body? At what moment did you realize that language could also be material?

I understood it in Tel Aviv. I realized that life tattoos us with invisible ink on our skin with words and messages. If you change a comma, you change the Universe.

Your figures seem to be made of silence and air. Are you trying to represent absence or to make the invisible visible?

I am Mediterranean, and I have always worked on the friction of opposites: body and soul, light and darkness, matter and spirit, day and night, visible and invisible.

Have you ever felt that one of your works knew something before you did? As if you had sculpted an intuition you had not yet deciphered.

Countless times. The work demands intuition to pose a new question, engaging in permanent dialogue between the hermetic and the enigmatic. I often feel envious of my works that can remain silent in wonderful places and contexts.

In exhibitions such as Mirall, inaugurated in September 2024 at La Llotja de Palma, where light seems more like a thought than a material, do you believe spirituality is built with forms or voids?

Spirituality lives from matter and transcends it. Years ago, seeing molten iron come out of the furnace to cast one of my sculptures, I realized that molten iron was practically only light—a fascinating light without form or weight. It was remarkable to realize that materials aren’t what matter most—it’s your attitude and dialogue with me.

What does it mean today to move someone, in a world that has often become blind to pain? Can art still offer shelter?

I believe that art must be like that place, in terms of space, matter, or spirit, to which you can always return. It is the indelible memory of the mother, the hand of the person you love, the smell of bread, the rain, or falling tears, etc.

You work with materials that seem eternal but are born from impulses so human, so fleeting. How do you reconcile that tension between the ephemeral gesture and the enduring work?

The work is a message inside a bottle. It conveys the message of the human soul that seeks to transcend and needs a container to protect it and help it reach the most remote shores, the most unknown territories.

What do you expect from your relationship with the future? Are you interested in leaving work for tomorrow, or rather, an echo?

Einstein said, “Why worry about the future, it comes so soon.” I agree with him.

Do you believe sculpture can still be a sacred space, a place of inner retreat, even in the heart of a city?

In my opinion, sculpture has the great capacity to create intimate and personal spaces with each viewer. Although it seems like a contradiction, I have always sought to generate intimacy in public space.

Behind the Walls became an urban icon in New York. What were you trying to hide—or protect—with that eloquent gesture of covering the eyes?

It was a very complex political moment with the construction of walls and barriers in many parts of the world. I thought it was important to highlight that the worst walls, the tallest walls, are our own hands when we do not want to see reality and hide behind them with a thousand justifications.

Together, installed at the Venice Biennale, took place inside a church. How do you feel about intervening in sacred spaces with works that also seem to seek the sacred?

Together was a project created for Chichester Cathedral in England and later traveled to the Basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore during the Venice Biennale in 2015. The work is a hand in the classic posture of blessing, built with alphabets from different cultures around the world. The hand itself is also a form of the alphabet used in all traditions. Together is a hymn to everything that unites us in spirituality, regardless of our cultural or religious origin.

If you could install a work in an unprecedented place —such as a submerged cathedral, a sleeping forest, a lunar station—which would you choose and what emotion would you seek to provoke?

In the water again. I always think of water as the great public space. It is a place that, without belonging to anyone, belongs to us all–seas, oceans, rivers, lakes, rain, tears.

Are you interested in exploring more ephemeral formats, where the work disappears like a sigh? What possibilities does that ephemerality open—or close—compared to the permanence of stone or iron?

I have worked on numerous occasions with ephemeral materials such as snow that melts, light that disappears with the light, silence filled with sounds, water droplets striking cymbals… In all my opera projects, which are born and disappear in each performance.

Do we still need monuments, or should the art of the future be built with invisible matter, like emotion, memory, or breath?

For many reasons, perhaps art is more necessary today than ever before. In any case, we will always need the artist’s intervention, creating elements —in one form or another— that help protect and preserve the perfume and soul of our society.

Your works are part of the everyday landscape of thousands of people, but few know who created them. How do you feel about that paradox of being profoundly intimate and yet anonymously universal?

I believe that creation is ultimately a way of breathing with society, of vibrating with it. This is my quest and my intention.

How is a poetics built that does not depend on language, that can move people in any culture or country?

Poetics is built by trying to reach the deepest part of your origins, and thus caressing the origins and roots of others that connect and merge with yours in the depths of being.

In Talking Continents, the words float, separate, and are not understood. What does that fragmentation of language say to you?

As François Rabelais said, words float in the middle of the sea, frozen in the cold air after being uttered, and are no longer heard. In the heat of the day, they begin to drip into disconnected sounds falling onto the ship’s deck like precious stones. The sailors ask their captain to sell them words, and he replies, lawyers already do that. I will sell you silence —and at a higher price.

Is there any emotion you have not yet managed to sculpt? Any silence you have not yet been able to materialize?

I suppose so. I am not aware of it. I go to the studio every day, perhaps to find it.

If you could sculpt yourself today, without mirrors or photographs, only with what you feel, what material would you choose and what part of your body would you leave unfinished?

I would work simply using balance weights bound together, totaling my body weight.

In the exhibition Inner Matter, themes such as identity, the fragility of the human condition, and spirituality are addressed. How do these concepts intertwine in your creative process, and what do you wish the viewer to experience when facing these works?

Above all, I use the exhibition as a mirror in which each viewer sees themselves reflected and decides to seek all the beauty hidden within them.

The show at Espacio Fundación Telefónica covers more than 30 years of your career. Looking back, how do you perceive the evolution of your sculptural language, and what constants have remained unaltered in your work?

It has been a very interesting experience to realize that over these thirty years, there has not been an evolution but rather an expansion. The main subject of my work has always been the human being, and over time, concentric circles have been created that expand around this persistent central idea.

This interview was originally conducted in Spanish and has been translated into English for publication.

All images courtesy of the artist.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista