Artist Bio

Benjamin Shine studied fashion design at the Surrey Institute of Art and Design and Central St. Martins in London. In 2003 he set up his creative studio, where materials, techniques and constructional ideas continue to inform his diverse portfolio and multidisciplinary approach.

Benjamin’s work has attracted a range of clients encompassing fashion labels, product and interior manufacturers, international arts and design institutions such as the Crafts Council, UK and the New York Museum of Arts and Design. Global brands include Givenchy, Barclays Wealth, MTV, Eurostar, Deutsche Bank, Coca-Cola and Google.

To date, Benjamin has won the Red Dot Design Award, the Enterprising Young Brit Award, and the Courvoisier Future 500 Art & Design Award.

INTERVIEW

Artist: Benjamin Shine

You don’t classify yourself as a traditional painter or sculptor. How would you describe the content of your work? What techniques do you work with?

I actually think of myself as a creative explorer and inventor. At heart I’m an ideas person, and while my work often gets classed as art, painting, sculpture or design, it’s all a form of invention and creative thinking. I have a constant desire to develop ideas that are fresh and worthy of existing; and if the end results provoke the reaction “How?” or “Wow!” at the very least, then I’m satisfied it has connected and made a positive impact on a person.

How did you become interested in fabrics?

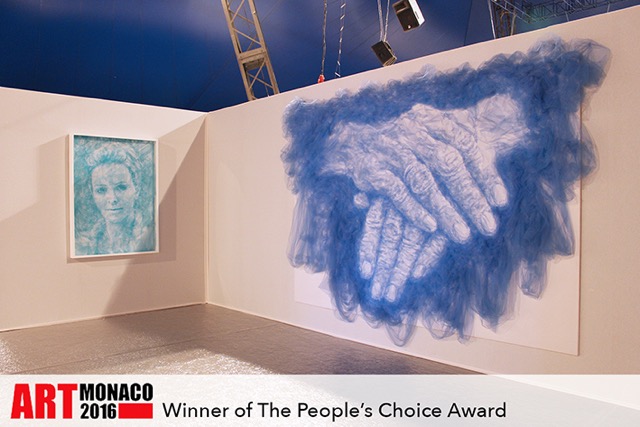

When I studied fashion design at the Surrey Institute of Art and Design, and then at Central St. Martins, I was quite obsessed with creating clothing from a single length of fabric. The pieces were very technical and required precision cutting in order to balance all the seaming perfectly. While I loved constructing clothes in new ways, I saw even more potential in fabric as a medium from which to create ideas away from the body. I saw it as a sort of three-dimensional paint to create forms and images. The tulle technique is the most recent development in my quest to bring the painted line to life through fabric. I have worked with torn strips of tulle in early pieces, but it wasn’t until I saw a crumpled ball of it on my studio floor that I noticed its potential. When I pressed it under glass, various tones became apparent from the layers of folds, and I began to test ways to create identifiable images from those folds. Much of my work explores one-piece construction, and the tulle technique epitomizes this train of thought. A single piece of tulle is manipulated into an image.

What and who inspires you to create?

Sometimes it’s the simple process of being given a brief that sparks ideas in a particular direction. Other times it can be a conversation. But mostly, as my work progresses and fills certain gaps that I‘ve wanted to fill, it exposes other gaps to investigate! Once I feel somewhat satisfied that I’ve reached a particular point with an idea, I feel the urge to do something that is somewhat removed from, or contrasted with what I’ve done before—something that will challenge me again.

Your portraits are made out of tulle. How do you shape the pieces?

The tulle portraits are created from a single length of tulle fabric. A long length of about 20 meters is piled onto a canvas in a dense, voluminous layer. I start by moving the tulle around to define the basic tones. Then, I work on the detail by either pressing and manipulating it with a hot iron (to bond it), or hand sewing it into place.

What’s the hardest part of the sculpture process, and how long does it take you?

The most challenging part of the process is finding the organic sense of flow and movement within the piece, making sure that it does not feel forced. With the highly detailed portraits, it’s always the last five percent that can take an enormous amount of time. I may minutely tweak the eyes or other fine facial details to be sure that it looks like the person being depicted. The time spent is generally relative to the scale of the piece; but usually a portrait takes several weeks to complete. I often keep it hanging in my studio for longer, as I sometimes notice incidental things once I have experienced a bit of distance from it.

What do you enjoy doing when you are not making art?

Outside of making art, there’s very little that goes on, as art happens to provide me with a lot of enjoyment and satisfaction! Still, I do try to spend time with family and friends whenever I can.

Where is your studio and what does it look like?

My main studio is in Australia. It’s essentially a big white box, and I often have up to 15 pieces-in-progress on the walls at any one time. There is also one wall of windows, which are sometimes diffused to create a very large light box for backlighting the installation pieces and sculptures. In recent years I’ve also enjoyed renting studios in the countries where I have projects to complete.

What was an early failure that discouraged you? How did you overcome it?

Probably too many to mention! But I learned early on that nothing is ever really a failure in the sense that it was useless or a waste of time. Secondly, to have a number of projects in development at the same time takes the sting out of any that are lagging or not working out. At least a feeling of achievement can be felt via other projects that are doing better!

Creatively, where do you see yourself in the next decade?

Hopefully, I will still be pushing the edges of my comfort zone and unearthing new discoveries.