In the contemporary landscape, Levan Songulashvili emerges as an artist who weaves the personal and the collective into a profoundly introspective visual narrative.

Born in Tbilisi, Georgia, in 1991 and now based in New York, his multidisciplinary practice spans painting, drawing, installation, video, printmaking, and sound, exploring themes of transformation, identity, and the tension between individuality and collective existence.

Influenced by philosophy, mythology, and personal experience, Songulashvili creates works that invite reflection on the human condition, blurring cultural and emotional boundaries. His vision rejects conventional divisions, embracing a perception of individuality that transcends categories of origin, race, or gender.

Recognized as one of the great emerging talents of his generation, his work is part of major public and private collections worldwide, including the Brooklyn Museum, where he is the first Georgian artist to be included in the permanent collection. He has been signed by leading international galleries and exhibited at institutions such as the Royal Academy of Arts, Saatchi Gallery, Sotheby’s New York, and the Georgian National Museum, among others.

He collaborated with the legendary composer Giya Kancheli, who named his final composition after one of Songulashvili’s paintings, and took part in large-scale visual projects for Amarta magazine alongside Issey Miyake.

Beyond the visual arts, Songulashvili writes essays and composes music as a self-taught musician, deepening his exploration of sensitive languages.

His work, deeply human and attuned to the cycles of loss, resilience, and renewal, signals a voice poised to leave a lasting mark on contemporary art in the years to come.

An Interview with Levan Songulashvili

By Carol Real

Your canvases often reveal a solitary figure standing against a tide of conformity. What does this “brave” persona represent in your own journey of self-discovery and creative defiance?

“Igi” is a short story written by the Georgian writer Jemal Karchkhadze, first published in 1977. Igi is a prehistoric tale of the first artist and thinker who discovers the power of creating images.

In a rigid society, Igi begins questioning the world, awakening a sense of wonder that sets him apart. His newfound perspective clashes with the Chief and his followers, who reject any deviation from tradition. As conflict unfolds between progressive thought and brute force, Igi embarks on a lonely and painful journey toward free will and the essence of being. This vivid narrative explores a strange yet familiar world, offering insights into questions that still haunt humanity.

I’m intimately familiar with silence and solitude as inner states, yet I am drawn to depict densely populated, dynamic compositions. I’ve always been fascinated by observing people, both as individuals and as members of a collective. The tension between personal identity and mass behavior is a recurring theme in my work; when the individual merges with the collective, they become part of a greater whole—many dissolve into one, and one expands into many. Yet history is not shaped by the masses, but by singular individuals whom the masses choose to follow. Still, those who rise to power often come to resemble the very figures they replaced. Systems are dismantled in the name of change, only to be rebuilt with familiar structures—and so, history repeats itself. However, the individual remains pivotal—the one capable of breaking the cycle, first and foremost through the power of the mind.

Jean-Paul Sartre once said, “If you are lonely when you’re alone, you are in bad company.” I am not lonely, but I am often alone; I am the only child of a single mother. I began drawing in early childhood—instinctively, wordlessly—much like a prehistoric human, like Igi, long before I could speak. Since then, visual perception, close observation, and the impulse to translate experience into image have become essential to how I move through the world. Painting requires solitude. It is in isolation—both spiritual and intellectual—that I evolve. In silence, I think more than I speak. I feel more attuned to nature. It is in these quiet states that new work begins to surface.

In your work, the interplay of societal power dynamics and personal narrative is compelling. How do you transform complex social themes into intimate, almost conversational, expressions on canvas?

Georgia, situated at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, is a land of profound cultural and geographical contrasts. Cradled by the Caucasus Mountains, its landscapes stretch from alpine highlands to Black Sea shores. This natural diversity shapes not only the terrain but also the people, reflected in the rich tapestry of dialects, culinary traditions, music, and aesthetics across its regions. The Georgian language and its unique alphabet belong to the Kartvelian family, unrelated to any major language group, underscoring the country’s deeply rooted and singular identity.

For millennia, Georgia stood at the confluence of empires—Persian, Ottoman, Mongolian, Russian—yet it preserved a distinct autonomy of spirit. It endured Soviet rule, but was among the first republics to rise in resistance. The massacre of Tbilisi on April 9, 1989, when Soviet forces killed peaceful demonstrators, marked a national rupture—and a personal one. My mother was among the protestors. I was born two years later, into a country struggling to reclaim itself. As a child, I marched with her during the Revolution of Roses in November 2003, and later stood with my generation before Parliament, still demanding freedom.

These experiences shaped my understanding of how memory, trauma, and identity are entangled —how the personal and political are inseparable. My work explores themes of migration, mythology, collective consciousness, and the human instinct to resist erasure. I am drawn to the universal within the specific—the recurring patterns of resilience and reinvention that echo across time and culture.

Georgia’s cultural position—neither fully Eastern nor Western, but uniquely its own—mirrors the space my practice occupies. While my work may resonate with both traditions, it resists singular definitions. It emerges from a place of convergence, where cultural boundaries blur and something universal can take form. I don’t perceive the world through divisions of skin color, gender, or national origin—I see it through the lens of individual presence. Borders, to me, are human inventions—not just geopolitical, but intellectual and emotional.

Now based in New York, I see the city as a condensed world, layered with histories, dislocations, and dreams. It offers a vantage point from which to examine what it means to belong, to be displaced, and to carry memory across continents. My practice translates these questions into visual form, not to provide answers, but to create space for deeper reflection.

Your mother’s strength and her unwavering presence have clearly shaped your narrative. How does her memory continue to influence your exploration of identity and resilience on canvas?

There’s a story I’ve never shared—not even with my closest friends. The early years of my artistic journey were steeped in black and white. Nearly all of my childhood drawings were monochrome. People assumed it was a stylistic choice—that I simply preferred the starkness of black and white. In truth, it was born out of necessity.

My mother raised me alone in Tbilisi during the turbulent 1990s. The newly independent country quickly descended into chaos. What followed were years of deep economic hardship and uncertainty. Oil paint was an unimaginable luxury when my mother was fighting simply to put food on the table. I couldn’t even dream of canvases, brushes, or color. So I drew with pencils on scraps of cardboard, but I drew constantly. On school chalkboards, on asphalt with stones, on desks, in math notebooks, in books, on wallpaper, doors, walls—anywhere I could. I drew every single day.

One day, my mother said something I’ve carried with me ever since: “If you can find color in a black-and-white world, your drawings will become paintings.” She was right. Over time, black and white became an extension of my inner world. I learned to see every tone and half-tone as color. Eventually, others began to see it too, immersing themselves in my monochrome universe and discovering unexpected hues within it.

In Tbilisi, there’s a small bridge where artists gather to paint and sell their work. One day, my mother brought a few of my drawings there. She told them about her little artist at home, gently asking if anyone had leftover paint, used tubes they no longer needed. That’s how she collected those precious remnants of color, one by one. And that’s how I painted my very first color piece. I remember the feeling vividly—it felt like magic. Like discovering alchemy.

In 2020, returning to Georgia to be with your mother during a profoundly challenging time, what inner shifts later surfaced as the textures and motifs that resonate so powerfully in your art?

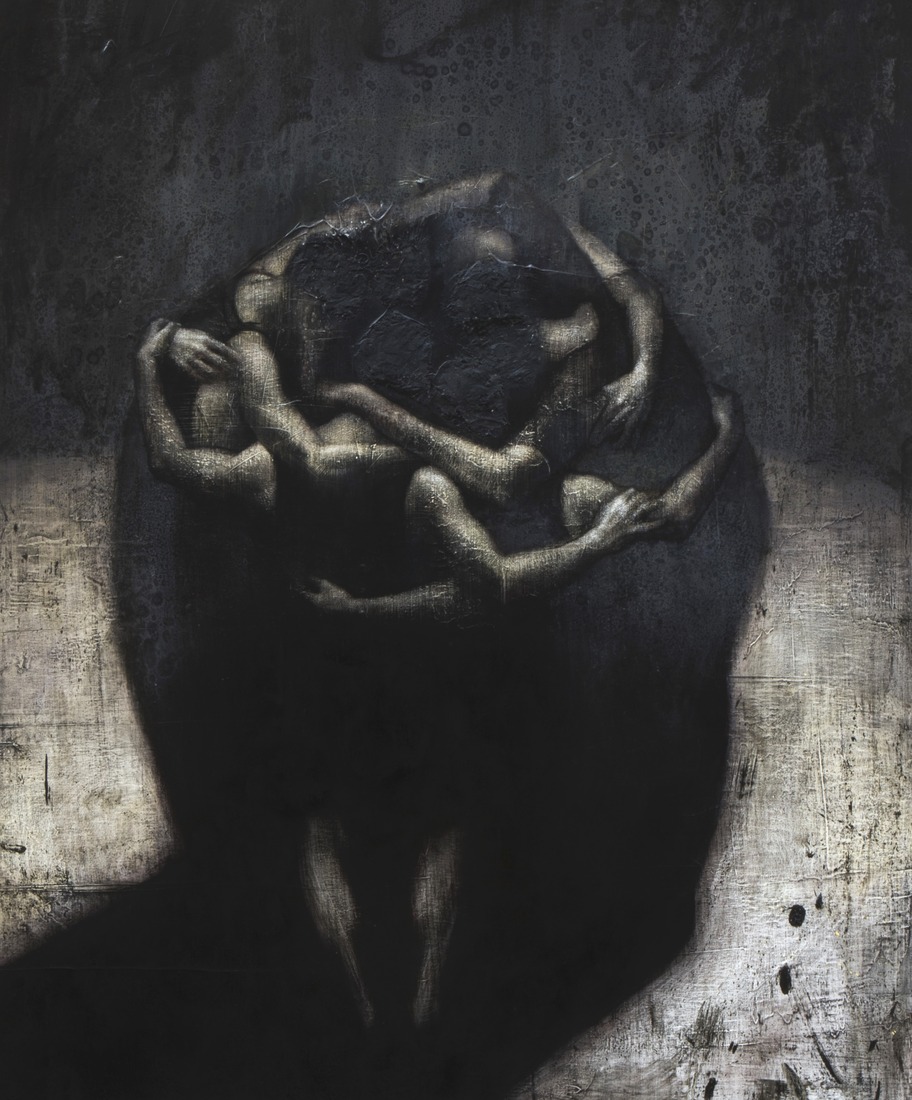

The day after my mother passed, I caught myself speaking of her in the past tense. In that instant, I understood something irreversible: she, who had always existed in the present for me, had shifted into memory. And still, within me, she remains ever-present. When you no longer have a parent, you are no longer a son. Her death marked the end of my childhood. I closed my eyes with her, and when I opened them again, a man was born.

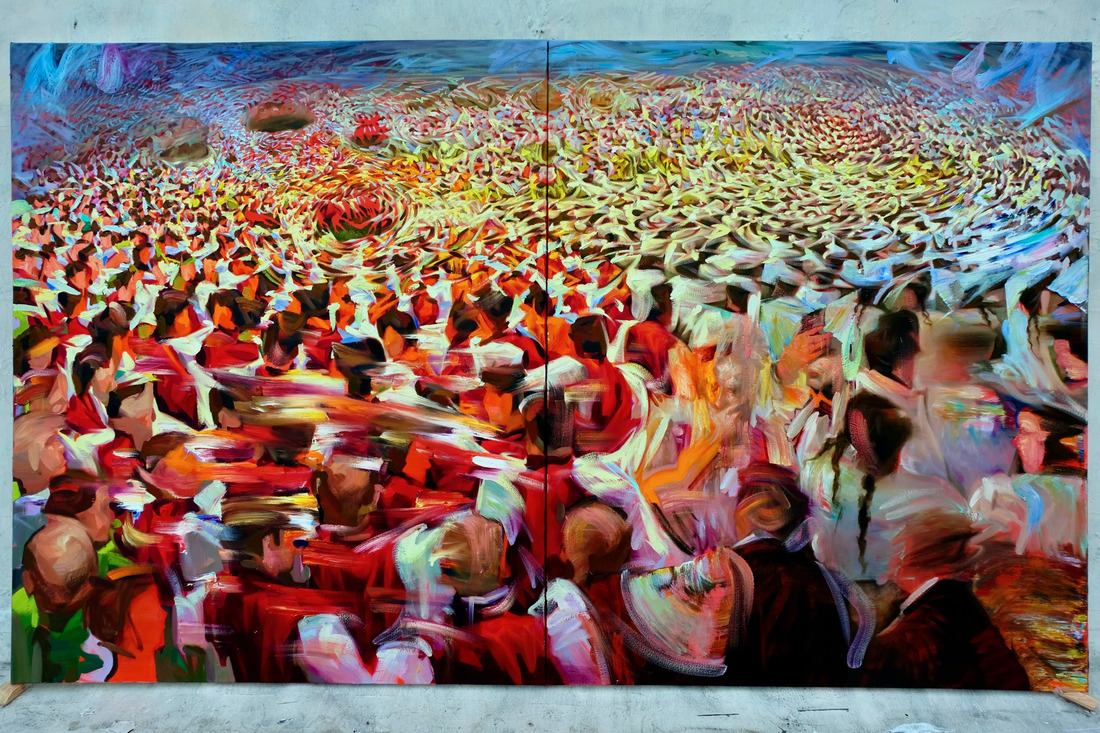

Unlike my previous works, Elysium (2020-2021) follows a unique path, encapsulating the stages of a deeply personal and transformative journey. The piece evolved over time, beginning before my mother’s diagnosis and continuing through the course of her illness. After a period of mourning, I was finally able to complete it for my museum solo exhibition, Triptychos (2021).

In ancient Greek mythology, Elysium symbolizes the afterlife. In my interpretation, the idea is reimagined through a contemporary lens, portraying humanity as a collective force in constant transformation. This abstract-figurative work expresses dynamic, kinetic movement through bold brushstrokes and a vibrant color palette. Pixelated figures interlock like puzzle pieces, forming a cosmic vision of the universe from a bird’s-eye view. A meditation on birth, death, and renewal, Elysium invites viewers to reflect on their own lives and the invisible ways in which our experiences are interwoven.

Since 2020, I have signed every work with two names: mine and my mother’s. She is the author of my being—and through me, the quiet co-creator of my art. One day, when I too leave this world, the works will remain. With them, two names will continue to live: Levan (Khatuna).

Opening that massive exhibition in Georgia on the anniversary of her passing appears to be both a tribute and a turning point. How did the interplay of personal grief and public celebration shape that pivotal moment?

The Georgian National Museum was the first museum my mother ever took me to as a child. I still remember her leaning in and whispering, “One day, your paintings will hang here.” She didn’t live to see that moment. But it felt only right that the exhibition honoring her memory would be held there—in that same sacred space—and that it would feature the very painting she watched me create in the final days of her life, Elysium.

Organized by the Window Project Gallery and the Georgian National Museum, the exhibition opened to the public without revealing its tribute to my mother. It was never announced that only a single painting would be shown, nor was the story behind it revealed. The piece offers no literal narrative. Thousands of visitors came each day—not only from across the country but also from neighboring nations—to experience the show. Yet, standing there, surrounded by so many people, I felt the deepest, existential solitude I have ever known. That feeling fades the moment I close the door to my studio.

Music is a wellspring of inspiration for you. Can you recall a specific moment when a particular musical piece catalyzed a breakthrough in your visual narrative?

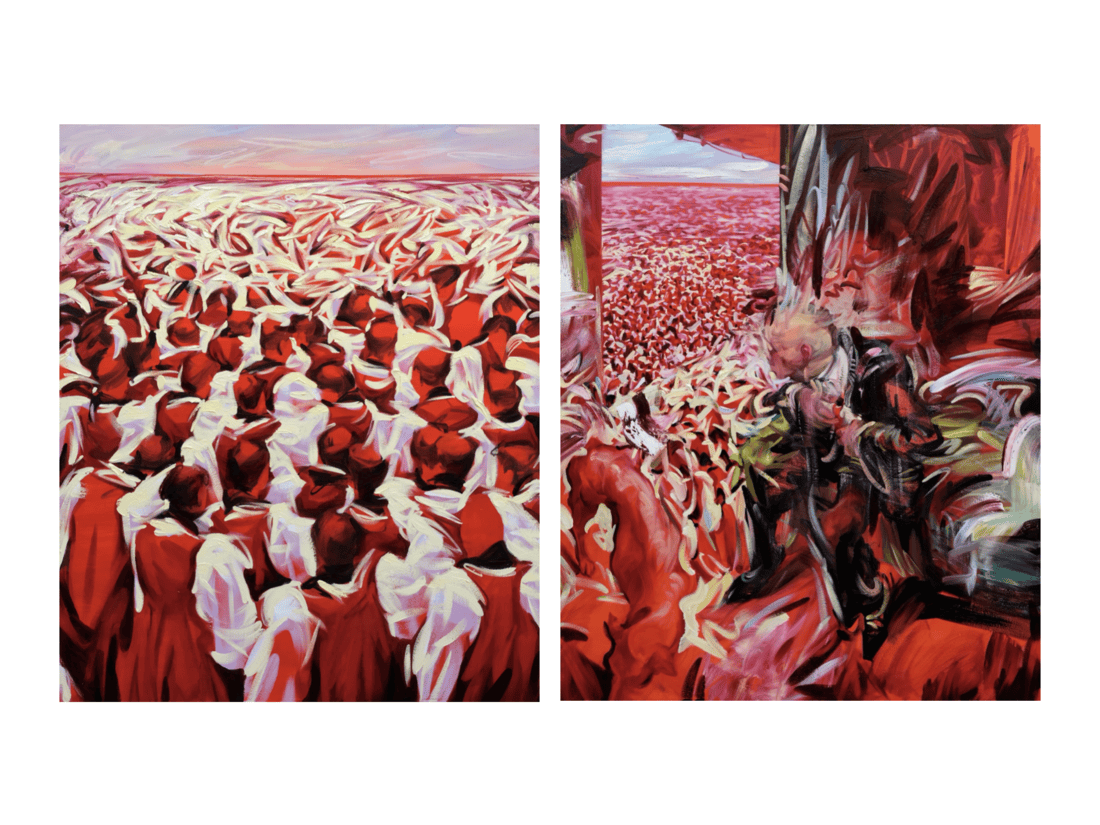

In 2015, amid the city’s restless energy, I attended a performance at Lincoln Center’s Appel Room—an evening featuring Steve Reich in conversation with Stephen Sondheim, alongside performances of Sondheim’s seminal works. Music often translates into images for me. That night, his rhythmic repetitions unfolded as chaotic black blotches and fragile white silhouettes—like Japanese ink bleeding through rice paper. At first, I saw penguins drifting across a frozen desert. Then, gradually, they transformed into a procession of migrating women. That vision became Idem et Idem.

Years later, in 2022, Iran erupted in protest against the hijab laws. Women burned their headscarves and lifted banners woven from their own hair. The images were hauntingly familiar—almost identical to what I had painted seven years before.

In a profoundly moving turn, in 2018, the legendary composer Giya Kancheli visited my solo exhibition and was deeply moved by one of the Idem et Idem paintings. He later titled his final composition after the work and incorporated it as a stage installation for its world premiere. He passed away the following year. It’s a moment that I carry with quiet reverence.

There is an almost cinematic quality to the way you depict movement and migration. Do you see your art as a visual journey that mirrors the transformative paths of the human spirit?

We, as human beings, exist suspended between the cyclical rhythm of life and the inevitability of existence. In this liminal space, we either yield to the current or resist it, drifting or daring to swim upstream. Like Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, life unfolds as a continuous passage from birth to death, marked by countless departures and returns. Each journey alters us. Each trial deepens our awareness. And with every return, we rediscover ourselves—transformed, reframed, redefined.

I often think of humanity as a vast library. Some lives read like dense, richly layered epics; others like fragmented, elliptical texts. As in Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, we move through shifting narratives and unfinished stories, navigating elusive meanings and disjointed voices. We resist the discomfort of ambiguity—the ache of not knowing, the longing for resolution. And yet, we press on, page after page, driven by curiosity and the need to make sense of what cannot be fully grasped.

In the end, when the book closes, we begin to understand: the journey was never about concluding. The story was complete not because it ended, but because we lived it. Perhaps it was never meant to have an ending at all. Red Horizons is one of my pivotal series, born in 2019 after a deeply introspective journey to Madrid. The horizon—both a visual and philosophical construct—became my point of departure. It is a line we see but can never reach, an illusion that marks the limits of our perception. On one side, I stand, captivated by its vast promise; on the other, another observer mirrors that same sense of awe. We are united in experience—bound by the shared act of searching—yet divided by the subjectivity of our realities.

The horizon embodies an ever-receding boundary that reflects a fundamental human paradox: our relentless pursuit of the unattainable. Yet it is not the destination that defines us—it is the movement, the transformation, and the quiet expansion that unfolds as we journey forward.

Sometimes I wonder whether art imitates reality, or if it’s the other way around. History offers uncanny moments when images from the canvas step into the world. In 2023, I painted a scene for the series: figures carrying the severed head of a statue through a desolate landscape. Months later, in 2024, I witnessed that same image come to life during the fall of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Damascus, Syria. These moments aren’t isolated.

What role does the human face play in your exploration?

I’m not drawn to specificity for its own sake. What compels me is the metamorphosis—the transformation of the specific into the universal, and the return journey from the universal back to the specific. I make a clear distinction between a portrait and a face: the portrait is tethered to the particular; the face belongs to the realm of the abstract. Abstraction speaks directly to sensation, which is why music, in its purest form, can move us so profoundly.

I rarely paint portraits of adults. They are already inscribed into the social fabric—society itself becomes the collective face of a culture. However, I’m drawn to the faces of children. Their features often feel abstract, even archetypal, at times evoking the timeless enigma of Egyptian sphinxes.

There is something profoundly mysterious in the way a child looks at an adult. Their gaze seems to reach beyond the surface, as if searching for something hidden within. As we age, we tend to lose this capacity. Adulthood often marks a shift—from depth to surface—and the return to those inner depths becomes far more elusive.

Your art operates at the nexus of movement and stillness, much like a conversation between sound and silence. How do you nurture this balance within the chaos of modern life?

In his 1882 work, Friedrich Nietzsche famously declared: “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.” Decades later, in 1915, Kazimir Malevich presented the painting Black Square. In 1952, John Cage composed 4′33″, a work consisting of three movements in which the performers do not play a single note. Composer and scholar Kyle Gann later described it as “an act of framing,” a work that “blurred the conventional boundaries between art and life.” Cage invited us to listen differently—to hear everything.

Together, these moments form a lineage of radical redefinitions: of God, art, sound, and meaning itself. They suggest that endings—however absolute—can also mark beginnings. Birth inherently contains the idea of death, just as death can open the way to something new. As the “Hymn of the Resurrection” declares: “By death, He trampled death.”

Even depression carries this paradox. Not in the darkness itself, but in what may follow once we emerge from it. Suffering can dismantle what is no longer vital and, in its place, clear space for something deeper, more essential, to take root. The myth of Sisyphus embodies the weight of futile repetition—labor that leads nowhere, effort without transformation. In contrast, the crucifixion is not simply an end, but a threshold: a descent that leads toward transcendence. It is the path through which suffering becomes elevation.

These two archetypes represent different dimensions of human struggle. One traps us in a closed circuit; the other breaks us open toward something greater. The difference lies not in the pain itself, but in our relationship to it—whether we are crushed by the weight, or transformed through it.

There’s a haunting truth in the notion that while the death of one can break the heart, the loss of many often fades into abstraction—numbers that numb rather than move us. I felt this profoundly during the pandemic, when daily death tolls were broadcast like weather forecasts. Behind each digit was a life: a voice, a history, a constellation of relationships—yet they vanished quietly, almost anonymously.

It was a sobering realization: how easily a human being can be reduced to data, and how grief becomes invisible beyond the circle of the bereaved. That experience deepened my belief in the essential role of emotional truth in art. Art has the power to restore feeling where it has been dulled—to reawaken sensitivity in a world increasingly shaped by algorithms, speed, and automation. It reminds us that we are, above all, human.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista

All images courtesy of the artist.