Artists Bio

B. 1926, MORCIANO DI ROMAGNA, ITALY

Arnaldo Pomodoro was born in 1926, in Morciano, Emilia Romagna, Italy. From the mid-1940s until 1957 he served as a consultant for the restoration of public buildings in Pesaro, while studying stage design and working as a goldsmith. In 1954 Pomodoro moved to Milan, where he met artists such as Enrico Baj, Sergio Dangelo, Lucio Fontana, and others. His work was first exhibited that year at the Galleria Numero in Florence and at the Galleria Montenapoleone in Milan. In 1955 his sculpture was shown for the first time at the Galleria del Naviglio in Milan.

Pomodoro visited New York in 1956 and traveled around Europe in 1958. While in Paris in 1959 he met Alberto Giacometti and Georges Mathieu, before returning to the United States where he organized exhibitions of contemporary Italian art at the Bolles Gallery in New York and San Francisco. In New York the following year Pomodoro met Louise Nevelson and David Smith. He helped found the Continuità group in Italy in 1961–62. The sculptor traveled to Brazil on the occasion of his participation in the 1963 São Paulo Bienal, where he was awarded the International Sculpture Prize. A solo show of his work was included in the Venice Biennale of 1964. In 1965 he was given the first of many solo exhibitions at the Marlborough galleries in New York and Rome.

The artist taught at Stanford University in 1966. In 1967 Pomodoro was represented in the Italian Pavilion at Expo ’67 in Montreal, and he received a prize at the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh. In 1968 he taught at the University of California at Berkeley; in 1970 he returned to Berkeley to attend the opening of an exhibition of his work that originated there and later traveled in the United States. During the late 1960s and early 1970s he executed commissions for outdoor sculpture in Darmstadt, New York, and Milan. In 1975 a Pomodoro retrospective was sponsored by the Municipality of Milan at the Rotonda della Besana.

Since the mid-1970s, Pomodoro has continued to gain renown for his unique engagement with fundamental geometric shapes, notably the column, cube, pyramid, sphere, and disc. His massive architectonic forms suggest a continual process of self-destruction and regeneration. His work has been the subject of numerous exhibitions at major museums, including Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville in Paris (1976), University Art Museum at University of California in Berkeley (1981), Columbus Museum of Art (1984), Hakone Open Air Museum in Kanagawa (1994), Centre of Arts in Cairo (1997), and Palazzo Magnani in Reggio Emilia (2005). In 1988 Pomodoro was invited to create a one-room installation for the Venice Biennale. He is perhaps best known for his outdoor public installations and their dramatic alteration of familiar vistas, including the Urbino Cemetery (1975), Amalienborg Square in Copenhagen (1982–83), Belvedere Fortress in Florence (1984), Cortile della Pigna in Vatican City (1989–90), United Nations Plaza in New York (1996) and Palais-Royal in Paris (2002). Pomodoro has lived a simultaneous career as a set designer for productions such as Aeschylus’ Oresteia at Teatro Massimo in Palermo (1983), Gluck’s Alceste in Genoa (1987), Ahmed Shawqi’s Passion of Cleopatra in Gibellina (1989), Eugene O’Neill’s Plays of the Sea in Rome (1996), and Puccini’s Madame Butterfly in Torre del Lago (2004), among others. The Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro, founded in 1995, for which Pomodoro serves as director, has been dedicated to the exhibition and funding of artists for over a decade. Pomodoro lives and works in Milan.

Interview

Artist: Arnaldo Pomodoro

By Carol Real

Early in your career, what masters and mentors influenced you most?

First of all there was Paul Klee, from whom I have perhaps drawn my signature style. When I started my research on the solids of Euclidean geometry, there was Brancusi, and then, Lucio Fontana with his new idea about space–and also Medardo Rosso, Boccioni, and Dubuffet. I won’t forget the lesson of Constructivism, which has been a very important movement for me—even more so than Dada or Surrealism. It is a reference that I have always kept close.

What was your childhood in Italy like?

I spent my childhood and adolescence in Montefeltro, an area between Marche and Romagna, whose border line is the river Metauro, which goes in and out each region like a serpentine.

I arrived in Milan in 1954. At the time, the city was full of energy, with a strong international imprint. It was on the cutting edge for theater, art, and music. I immediately started to associate with the artists and intellectuals who met at a bar called “Giamaica.” Meeting with Fernanda Pivano and Ettore Sottsass was fundamental, and, through them, I got to know American culture.

Do you think art is a skill we are born with, or is something we acquire from our surrounding environments ?

Ever since I was a boy I was attracted by matter—matter that I needed to touch and transform. I realized that my path must involve sculpting. But I must say that I was also strongly influenced by the landscape of Montefeltro, a wonderful part of Italy where stone and architecture are majestically integrated. It looks like the rocks, fissures, and the rest of nature are the remains of ancient cities.

What tough challenges have you faced as an artist during your career?

The artist looks deep inside–for himself. He is pressed by emotions and attempts to rid himself of his anguish and to feel liberated by doing his work. This is always a difficult road, sprinkled with lights and shadows.

What led you to work with bronze? What keeps you interested in the material?

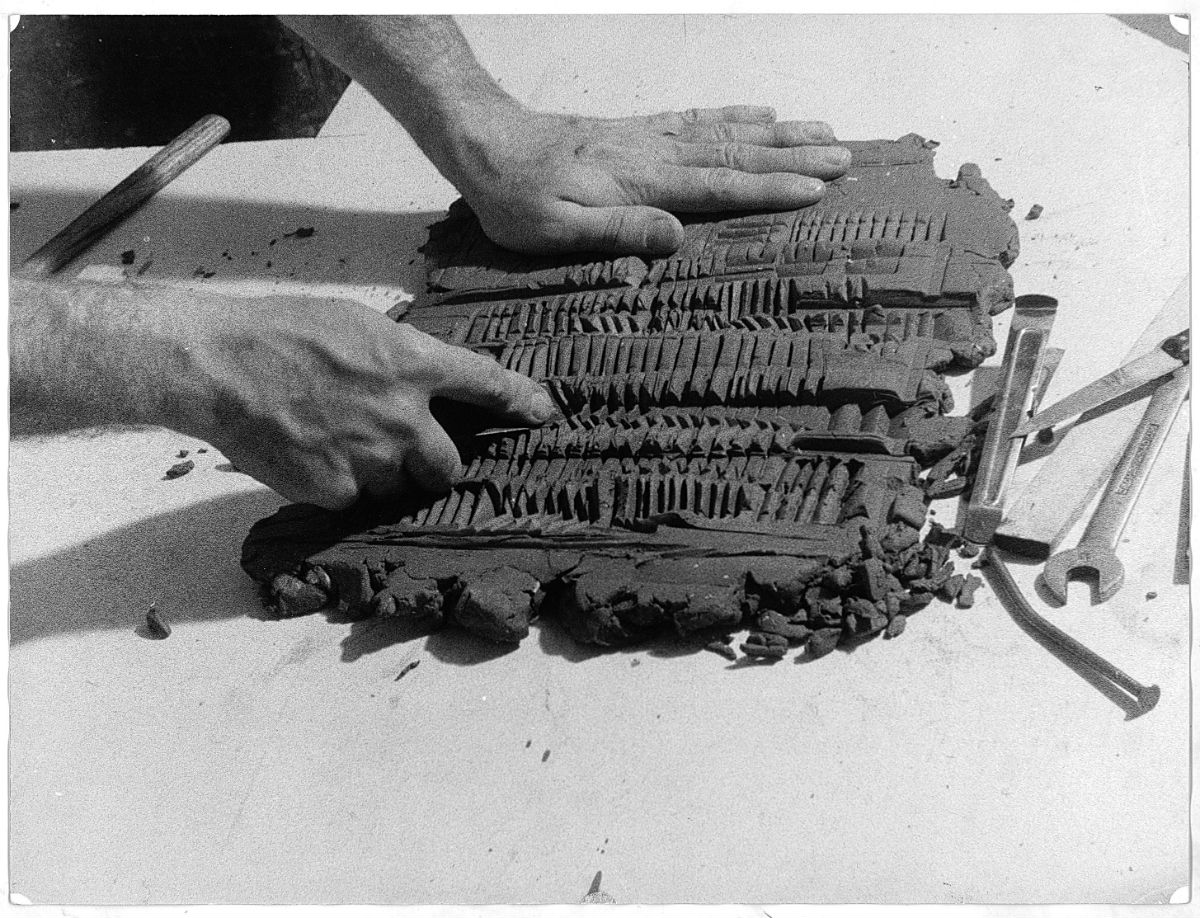

All metals fascinate me. I have used lead, tin, iron, copper, silver, and, in particular, bronze, which I prefer glossy and uncoated. It is the most appropriate material for my artistic language—the one that best expresses the specific contrasts of my sculptures.

Which one of your pieces are you most proud of? And why?

I believe that Large Disc [Grande Disco] is one of the most significant works of my career. It is four and a half meters in diameter with a weight of about seven tons, installed in Meda Square in downtown Milan, a city that seems to have adopted me.

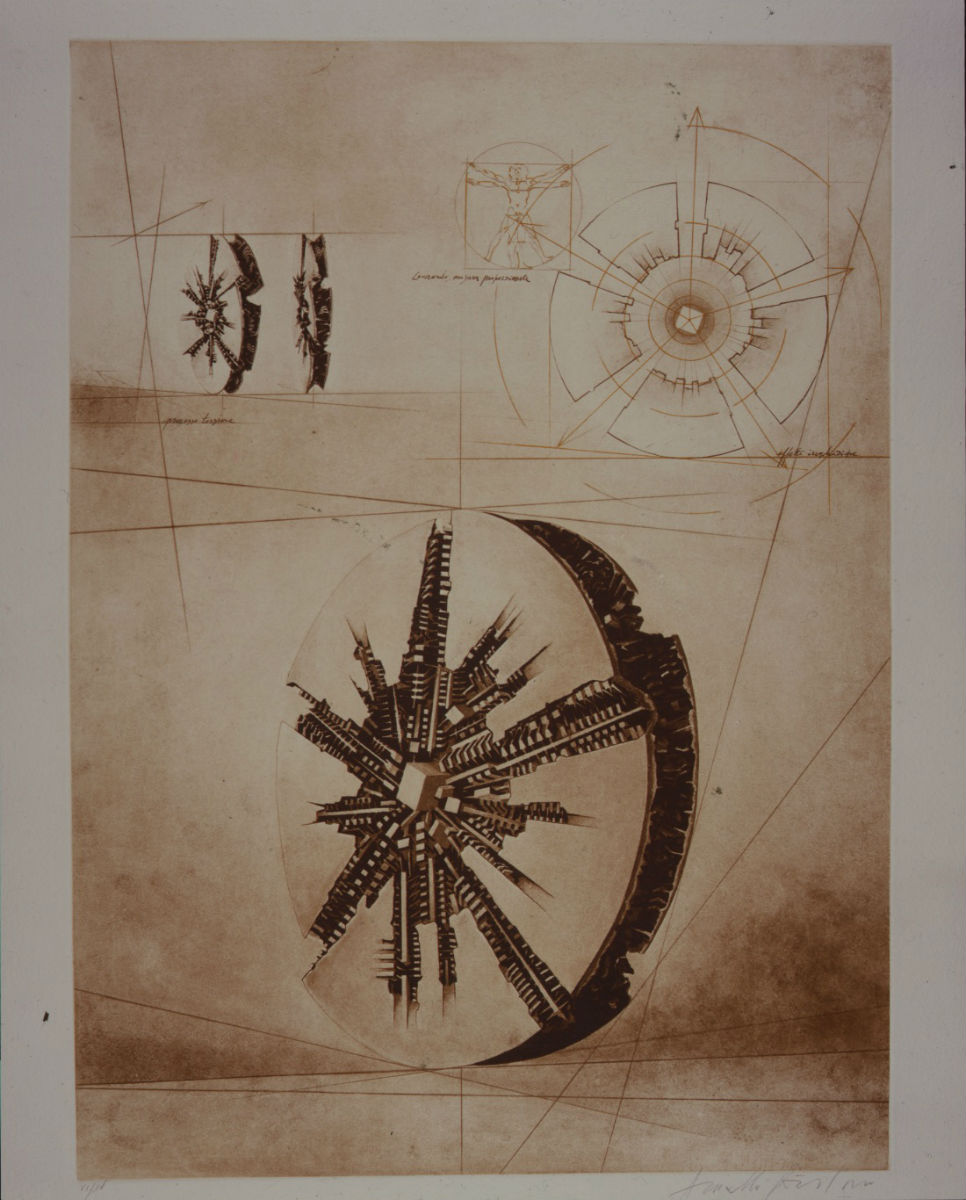

I tried to give the sculpture a sense of torsion to make it more alive, and I have represented the proportion of man that Leonardo has inscribed in a circle. Its positioning is the most successful part. The work has been placed the vital context of the city, and within that, it represents the city’s dynamism, optimism and solar strength.

You create art works that merge ancient symbolism with futuristic technology. The technology makes it possible to make excellent copies of sculptural works—as has been done with your Disco–allowing it to exist in many locations. Does this repetition turn a sculpture into an industrial object rather than an artistic one?

I believe that my works express both respect for the past and admiration for new discoveries, knowledge, and technology.

My way of working (typical of traditional, inventive working skills of craftsmen) excludes the use of mechanical techniques for reproducing the work. It is based on the classic method of lost-wax casting and requires particular care.

I think, however, that every form of expression is valid and has its own logic. Contemporary artistic research finds current solutions and techniques in an absolutely free way, as it was in all the great historical examples. The important thing is to exclude any purely show-off processes—those that are merely repetitive, commercial or trendy.

Have you ever designed a project that just didn’t work out or that was impossible to actually build?

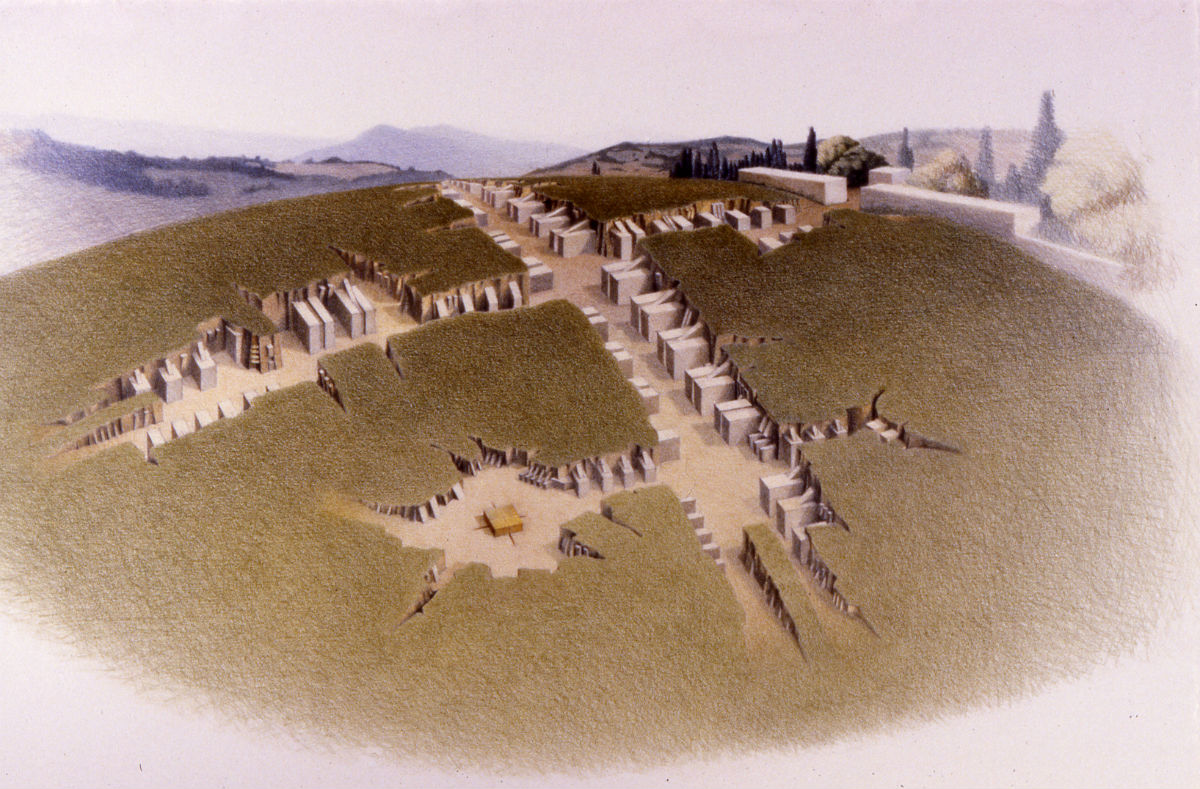

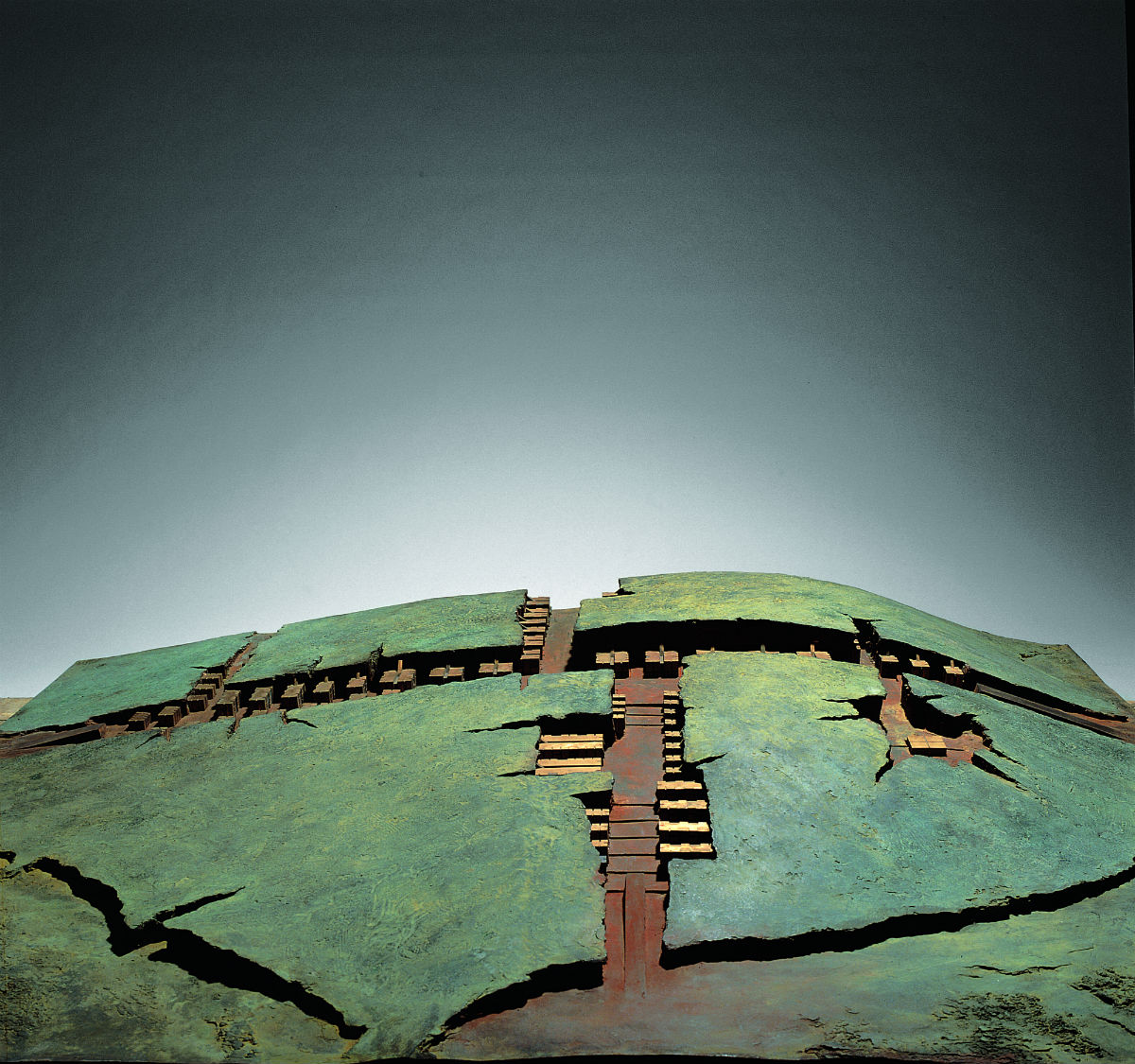

Yes, in many cases. Those are works that I have called “visionary projects.” They are projects for buildings (example: the Cemetery of Urbino), toys, spectacular machines, utopias. In general, they are paradoxical shapes that question an environment or a norm and reveal in a particular way the deep, complex connection between pure artistic research and the process of architecture and design. For me they represent a stimulus towards every possible spatial intervention.

In Milano you met artists such as Enrico Baj, Alberto Giacometti , Sergio Dangelo, Lucio Fontana, and others. Have you any memorable anecdote would you like to share with us?

I remember that Lucio Fontana suggested to my brother Giò and me a basement that would eventually become our first studio in Milan. It was on the corner of Via Visconti di Modrone and Corso Monforte, near his own. He often came to visit us and see our early works, giving us advice that we always considered very important. I remember his smile, so expressive and ironic, and his way of speaking that was simple, but always acute. He moved with vivid gestures, an intertwining of motions that seemed to relate to the neon arabesques he adopted as an artistic medium–before anyone else did.

He was an inventive, moving spirit animated all of his work.

Light and reflection are primordial in your sculptures. Describe your feelings as your process and imagination work in synchronization.

The starting point is always the desire to give shape to my imagination, and I believe that what I pursue in sculpture is really a new vision of reality. Therefore, when I focus on the work I am creating, I feel courage and vitality.

Usually family members working together tend to irritate one another. How was the experience of working with your brother Giò Pomodoro?

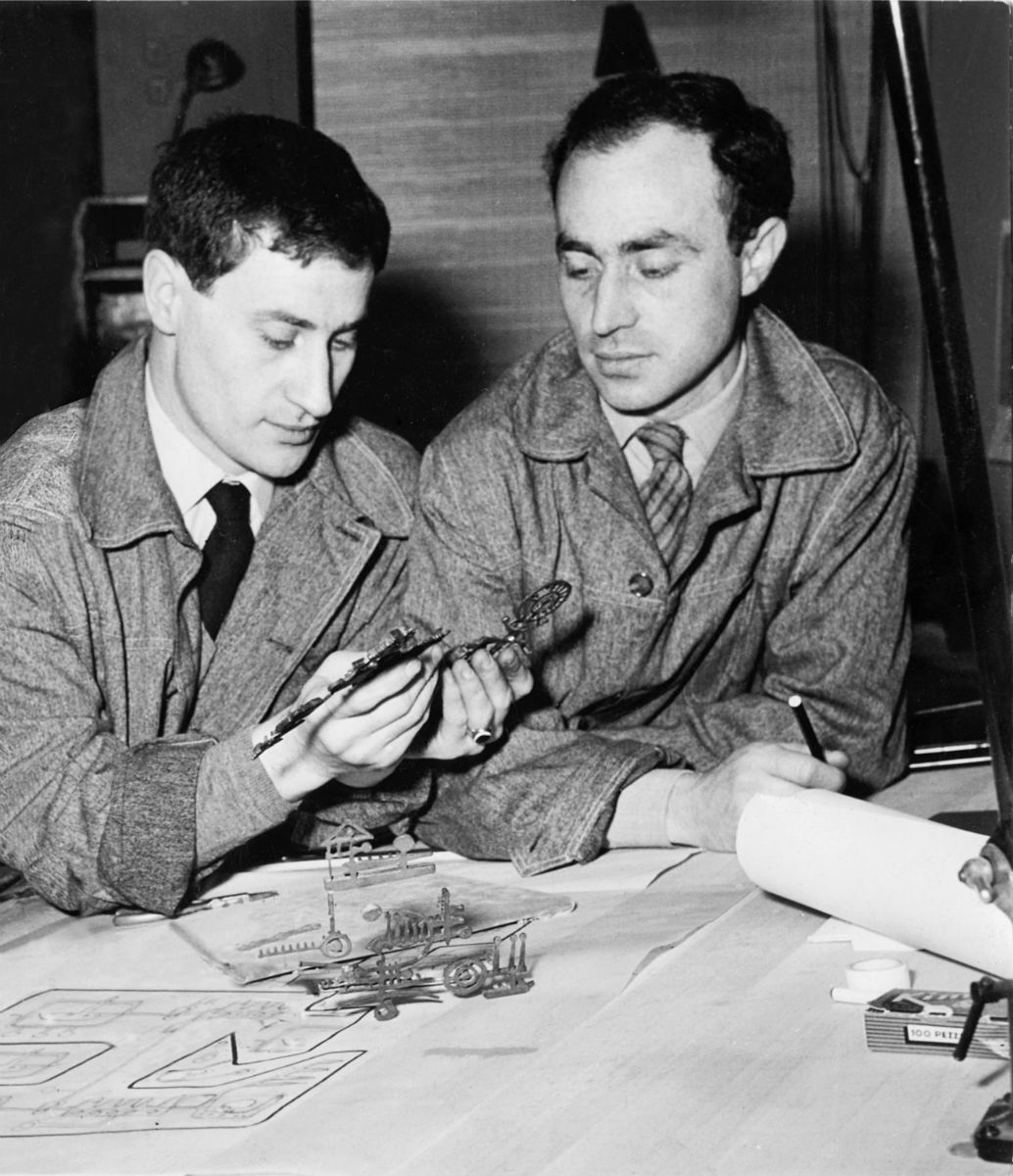

My artistic journey started with Gio’, and for years we shared the studio in a true creative partnership. Later our ways drifted apart, and each of us embarked on a more individual journey.

You once said that “The future of art is to integrate it with architecture.” You said, “The Renaissance is the best example of this unity. Today, architecture is often in competition with the artist. That should not be.”* Today, 30 years later, do you think that integration has finally been made?

*Retrieve article at www.nytinmes.com Pomodoro sculpture 1981

Art and architecture are two different ways of dealing with space. I think that three-dimensional works claim their own space within the greater space where one lives and moves and that there is always a close and complex relationship between art and architecture, particularly, between sculptures and cities.

The integration between the works of the architect and the sculptor, therefore, cannot fail, even though it is something that must be continually rediscovered through relationship that triggers debate and mutual stimulus.

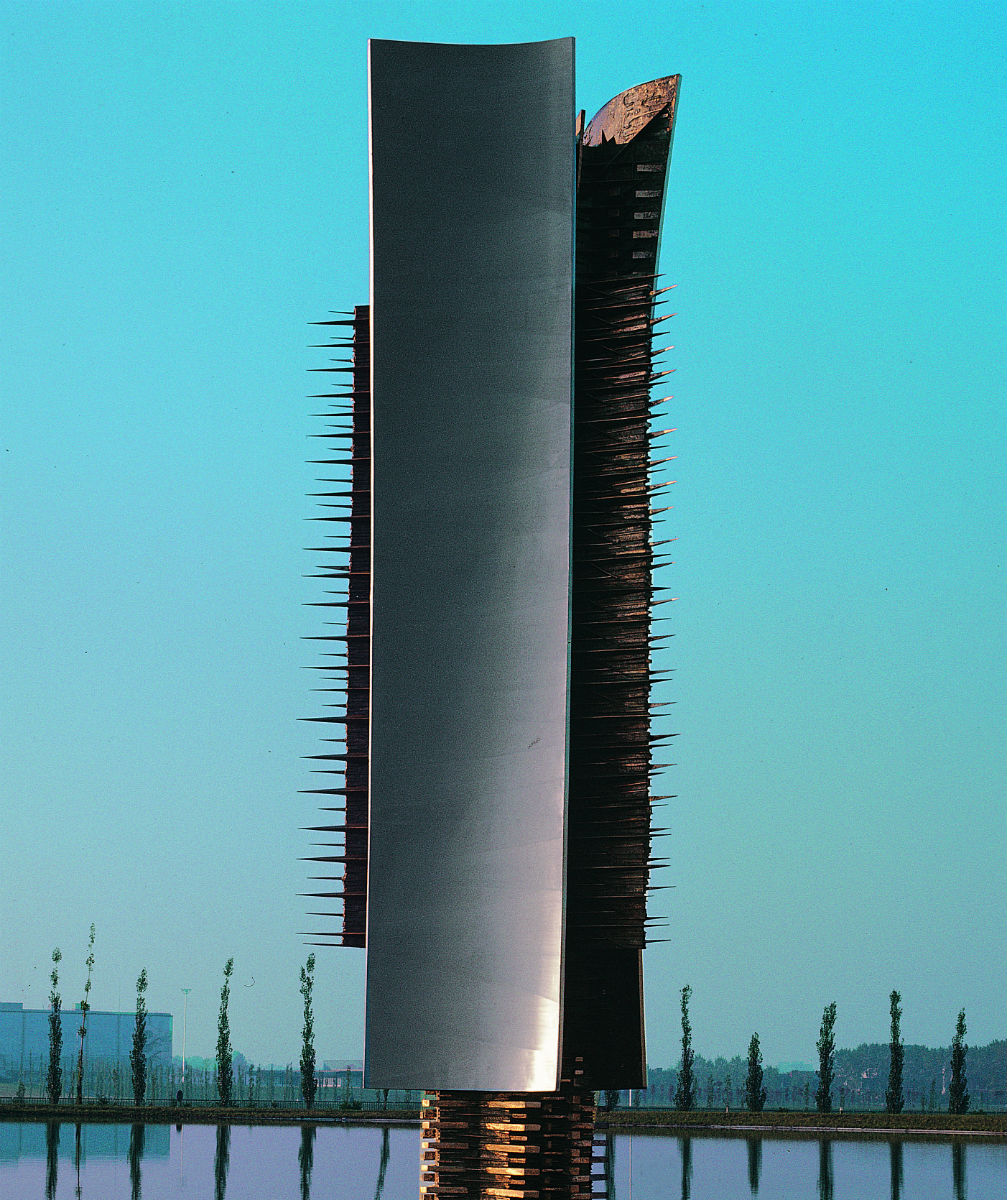

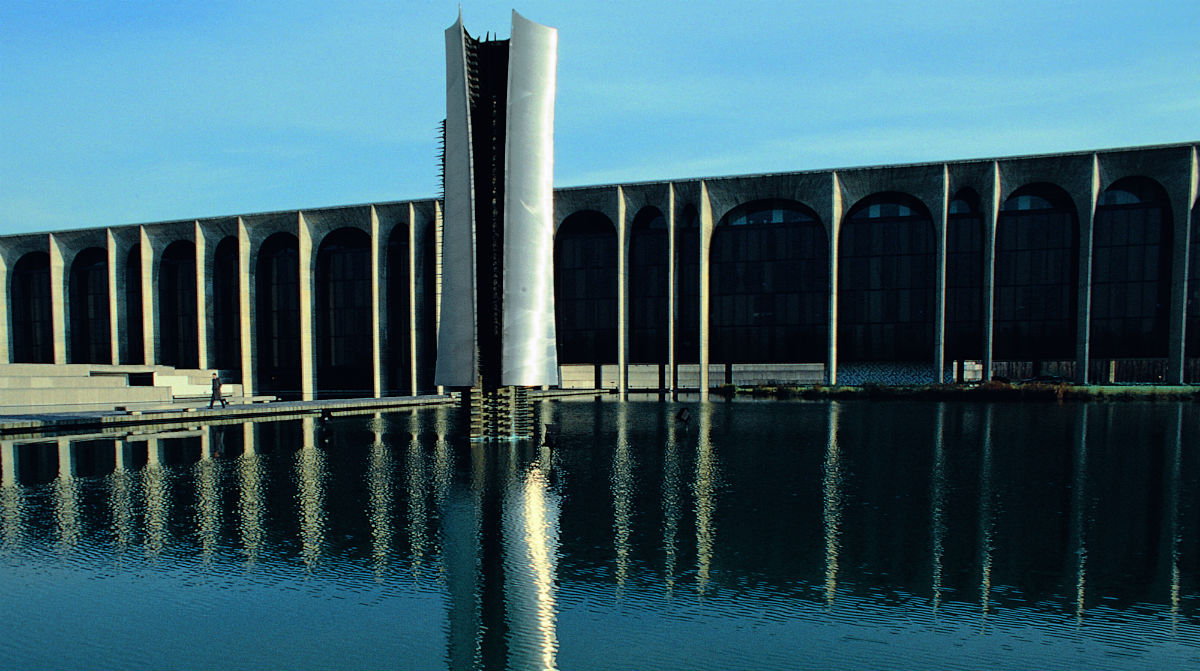

I have often worked with architects, and it was always a stimulating experience. In Segrate, the building that houses the publisher Mondadori has a dynamic, continuous façade of arches designed by Niemeyer. I thought of a sculpture, Column in Large Sheets, which projected activity and movement. In Copenhagen, for the sculptures for the garden opposite the Royal Palace, I worked together with Belgian architect Jean Delogne. The collaboration with landscape artist Ermanno Casasso has developed over time through several works: the large, concrete Solar Earthly Motion, plunged into the garden that encloses the Symposium of Minoa, near Marsala; the terracotta arch, called Arch in the Sky, in the Negombo spa-park in Lacco Ameno, on the island of Ischia.

To bring out the balance and harmony of architecture in its surrounding natural environment, there is my giant sculpture, Carapace, an enclosure for the winery at the Lunelli family estates (Castelbuono) in Bevagna, Umbria.

Your sculptures are seen in major public spaces all around the globe. Do you have a favorite? And, if so, why?

I would like to mention a work that seems to be completely abandoned at this point: the project for the new Cemetery of Urbino, inspired by the idea of equality for everyone in death and the return of the dead to the earth. After winning the City of Urbino competition in 1973, the project was not realized due to strong complaints voiced from certain local “noteworthy” places. Many representatives from the world of culture then took my side (Paolo Volponi, Giulio Carlo Argan, Bruno Zevi, Lea Vergine, for examples) starting a great debate in the press. But it wasn’t enough. However, I have not lost hope that this project may someday be built in another location in the world, because I am sure that it could be excellently placed in many other contexts.