Artist Bio: Christian Jankowski

Christian Jankowski, born in 1968 in Göttingen, Germany, is a contemporary artist whose innovative and thought-provoking work transcends conventional artistic boundaries. He studied at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg, Germany, and currently resides in Berlin. Jankowski’s artistic practice encompasses a wide range of media, including film, video, photography, performance, painting, sculpture, and installation.

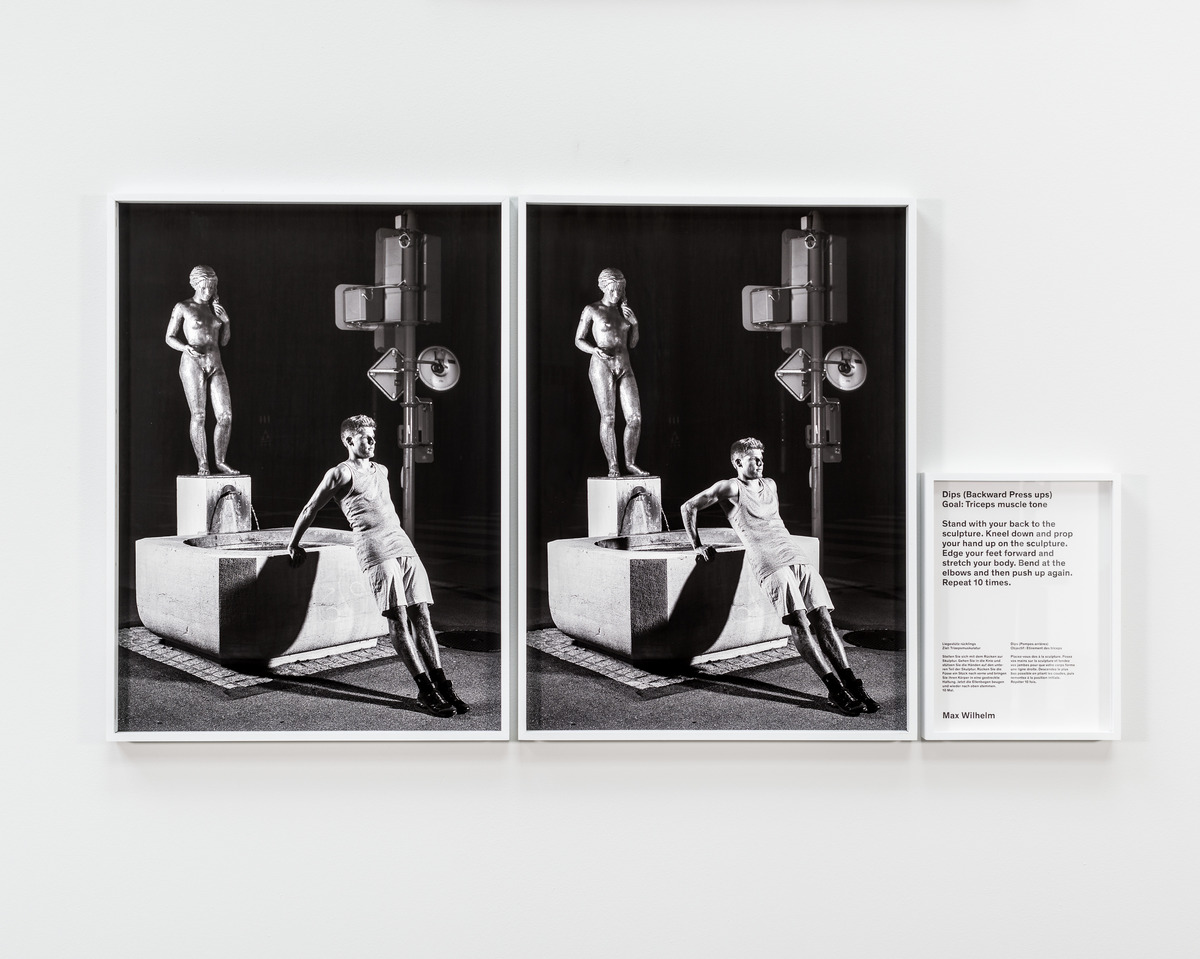

Jankowski is renowned for his unique approach to art, characterized by performative interactions between himself and non-art professionals, as well as between contemporary art and the world outside of art. These interactions serve as a lens through which he explores popular perceptions of art and engages with contemporary societal themes such as lifestyle, psychology, rituals, self-perception, competition, and consumer culture.

Throughout his career, Jankowski has collaborated with a diverse array of individuals, including magicians, politicians, news anchors, and even members of the Vatican. In each collaboration, the context and participants exert control over the development and final form of his work. This participatory element, combined with the use of mass media formats like film, photography, television, and print media, contributes to the populist appeal of Jankowski’s art.

Jankowski’s work can be seen as both a reflection and critique of a society dominated by spectacle, as well as a reflection and critique of art itself, which has sometimes succumbed to spectacle at the expense of its critical potential.

In addition to his solo exhibitions, Jankowski has participated in numerous group exhibitions and prestigious art events around the world, including the Venice Biennale, Whitney Biennial, and Manifesta, where he became the first artist to curate the 11th edition of the event.

Through his performative videos, sculptures, photographs, and installations, Christian Jankowski continues to provoke thought, question established norms, and create art that resonates with a contemporary audience. His innovative projects explore the evolving language of art, drawing inspiration from everyday life, technology, and the ever-changing dynamics of the art world.

An Interview with Christian Jankowski

By Carol Real

Could you share some insights into your early life and what led you to pursue art?

I was raised in a small bourgeois family, where my parents, though not particularly passionate about their work, prioritized investing in things that held significance for them, such as family, travel, and entertainment. This upbringing played a significant role in shaping my interests. Thanks to my parents, I discovered the joy of traveling and the value of experiencing new things firsthand, rather than solely relying on books. Our journeys not only took us to popular tourist destinations but also led us to explore archaeological sites, historical museums, and art museums. It was during these explorations that I developed a deep fascination for these subjects, which eventually aligned with my personal interests. Interestingly, my initial career aspiration was to become an archaeologist, driven by my desire to delve into ancient cultures. However, it seems I took a different path, delving into the most contemporary aspects of culture and society.

How did your time at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg influence your artistic development?

My time at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg had a significant impact on my artistic development. Initially, I had arrived with the aspiration of becoming a painter. However, quite early into my studies, I found myself deeply engrossed in meaningful conversations and interactions with some of the esteemed professors at the academy, such as Franz Erhard Walther and Stanley Brouwn, both renowned conceptual artists. Engaging in dialogues with them and listening to their insights gradually eroded my interest in my own naïve abstract paintings, which, though not entirely decorative, felt somewhat out of step with contemporary sensibilities.

I began to see more promise in immersing myself in performance art and utilizing video as a medium to document these performances. I suddenly realized that these one-on-one exchanges with others offered a richer and more profound reservoir of experiences.

In addition to the academic aspects, another valuable aspect of my time in Hamburg was the space I rented there–a shop front in a prime neighborhood. This space provided me with the opportunity to showcase my work without the necessity of relying on a traditional gallery setting.

In your work, you delve into the confluence of contemporary art and the “world outside of art.” What initially ignited your interest in this concept?

For quite some time, I had the sensation of being an outsider within the art world itself. I was intrigued by the notion of performance, but early on in these initial performances, I also started contemplating the role of being an artist as a profession akin to any other. It soon dawned on me that I desired to incorporate individuals from various professions as performers in my artistic creations. I believe that very early in works like The Hunt, where I assumed the role of ‘the hunter”–a time-honored occupation from a different era–I had already begun connecting the dots between performance and human activity, as well as the ceaseless activity of life itself, which can be likened to a lifelong performance: the organization of sustenance. Additionally, I grew up within an environment and during an era where selecting a profession was perceived as a profound decision. Thus, in some ways, I also opted to become an artist in order to keep a myriad of possibilities open to myself, for I believe that the essence of a fulfilling life lies in making choices. Being an artist allowed me to integrate all these potential ways of experiencing life by incorporating various professions into my artwork. With each new experience, I am afforded the chance to reevaluate my own principles, my own routines, and my own structures.

Could you share examples of the performative interactions you’ve undertaken with individuals outside the art profession as part of your artistic pursuits?

Regarding The Hunt, I previously mentioned my role as the hunter, which placed me in a rather conventional performance role, engaging in unconventional actions in front of a camera. However, as we proceeded with filming, a cashier who was ringing up the items I had “hunted” inadvertently became my initial professional collaborator. Her routine actions of billing, bagging, and requesting payment added significant depth to the work. It was not just my “wild” act of assuming the role of a hunter in a supermarket; it was her everyday actions that gave the artwork an additional layer of meaning. This layer delved into the systems, interactions, and social agreements that govern how we collectively adhere to certain rules in society.

Another example from my earlier works is My Life as a Dove. For the duration of an exhibition, I had a magician visit the gallery to transform me into a bird, returning three weeks later to reverse the transformation. The spectacle in this case was the artist himself taking on a different appearance. This project required collaboration with a professional magician to achieve the magical transformation. Furthermore, I aimed to convey the concept of another type of artist—the magician as an artist. Through this collaboration between artist and magician, I sought to push boundaries further and truly vanish, only appearing as a dove for those three weeks. To this day, nobody knows what transpired during that time.

In Strip the Auctioneer, I employed the framework of a Christie’s auction to develop a project where, instead of offering an art object, I requested items from the auctioneer—specifically, his clothing. The moment his shirt and pants were put up for sale, they transformed into artworks, each acquired by different collectors. This approach allowed me to explore systems, particularly those transitional moments where something shifts from one state to another. It raises questions about when the meaning and status of an object change. In other words, it involves working with frames, which traditionally delineate the inside as the artwork, with everything else relegated to the normal world beyond the white walls. By blurring these boundaries and expanding the frame’s perspective, I aim to offer viewers a broader understanding through these collaborative experiences.

You’ve collaborated with a diverse range of individuals, ranging from magicians to politicians. What attracts you to such a variety of collaborators?

Collaboration offers me something that I cannot entirely control, something I genuinely desire to experience. It’s a dialogue that involves relinquishing control and then regaining it. There have been instances where I’ve either exerted too much control or too little. For instance, sometimes I’ve been overly rigid in trying to establish a specific framework and steer a project in a direction I find intriguing, leading me to prematurely trim branches that I thought were my focus. Ultimately, it’s about finding the right equilibrium. On the flip side, I frequently find myself working in languages I don’t speak. In Romania, during Defense Mechanism, I had a group of Romanian military personnel attempting to breach a door until they unexpectedly found themselves in a group therapy session with a professional therapist. While filming, I couldn’t understand a word they were saying and had to rely on the hope that the conversation would take a positive turn; otherwise, it would need post-production intervention, as was the case with this particular piece. I had to trust the Romanian therapist to guide the group without losing control. However, when I encountered difficulties in the editing room myself, I brought in another therapist to review the material. Upon reviewing it, he remarked, “Of course, Christian, this therapist is going through a crisis moment. He’s overwhelmed by the soldiers armed with weapons and military uniforms invading his delicate healing space.” This allowed me to see the humor in one therapist’s commentary on another therapist’s office and eventually led me to incorporate the second therapist’s voice-over into the video, after working on the piece for over a year without finding a solution.

Can you provide further insights on how the role of context and participant control influences your artistic creations?

Each profession I collaborate with brings its unique perspective, focus, and vocabulary, which often manifests in the aesthetics of the final work as seen in mass media. I recognized early on the importance of engaging in a dialogue with the specific aesthetic and context surrounding the creation of a particular piece. It was essential to carefully select the medium that would best convey the essence of the performance. This approach was already evident in The Hunt, a very short video lasting maybe only a minute. It was edited in a manner reminiscent of how a knife might be advertised on a small monitor in a supermarket. I drew inspiration from these types of videos during the editing process, aiming to deepen the connection to the original context of its creation.

This commitment to preserving the connection to the context remained a constant in all my films, which essentially document various performances involving professionals such as sports presenters, TV talk show hosts, and Hollywood special effects creators. Decisions regarding the use of materials and techniques are always closely aligned with the context, rather than being merely simulated by me. Additionally, I appreciated the idea that the artwork’s circumstances could be distinct, as exemplified in the Karaoke project. In The Day We Met, the work was programmed into actual karaoke machines worldwide. People in Asia, Korea, Japan, or the U.S., although unaware that it was an artwork, interacted with it within their systems and unique contexts.

Could you share your approach to documenting your collaborative performances and explain how this documentation contributes to the widespread appeal of your work?

I center my attention on language and storytelling within the various formats I employ, whether it be video, posters, bronze sculpture, oil painting, and so on. I don’t perceive a significant distinction between working across these diverse genres; each possesses its own set of conventions and a distinct language for communication.

Similarly, when it comes to mass popular culture and mediums such as television, cinema, and the internet, we have collectively acquired the skills to interpret them. Utilizing these mediums enables me to captivate a broad audience because most people already possess the means to comprehend the work, in contrast to other forms of fine art that may seem less accessible.

Your work has been characterized as a simultaneous reflection on and critique of society’s preoccupation with spectacle. How do you manage to strike a balance between these facets within your art?

Spectacles are often perceived negatively due to their association with being inexpensive or seeking excessive attention. However, I believe that spectacle can also be quite remarkable. Consider religious storytelling, for instance; every miracle can be seen as a form of special effects–like walking on water. It’s an attention-grabber, and people naturally want to witness such phenomena. These spectacles challenge our rationality and stimulate contemplation.

Similarly, in the realm of sports, we encounter the spectacle of competition: the quest for speed, rivalries, and the commentary that surrounds it all. My work isn’t hesitant to explore these elements, even though they might seem populist or cult-like at times. I’m drawn to these media spectacles because I believe they merit contemplation. In my project Casting Jesus, I depict multiple representations of Jesus competing against each other to perform miracles in front of a Vatican jury. This work not only reflects on iconography but also delves into the values conveyed by television casting.

What inspired you to invite visionary entrepreneurs and thinkers from Silicon Valley to participate in Silicon Valley Talks?

Upon receiving an invitation from SFMOMA to engage in a project situated in Los Altos, within the heart of Silicon Valley, I began contemplating the reach and impact I could potentially have from this vantage point. Naturally, this led me to ponder the individuals who shape the essence of Silicon Valley itself. These are the innovators who present ideas to the world, secure investments, and ultimately influence the trajectory of the contemporary world.

My desire was to personally meet some of these distinctive figures, and thus, I extended invitations for them to deliver “TedTalk”-style presentations at a venue I established in Los Altos. However, I had a unique twist in mind. I encouraged these visionaries to delve into topics entirely unrelated to the Tech Industry, addressing subjects such as fly fishing, romantic relationships, and family holidays. Furthermore, I challenged them to approach their talks in two distinct phases: firstly, to craft their lectures, and subsequently, to reinterpret the content into the language of the tech world. For example, the fisherman’s catch is referred to as consumers and so forth.

Every profession possesses its own specialized jargon, a lexicon that exudes an air of mystique and understanding of domains we often find inaccessible. Our comprehension often relies on contextual cues, and in a sense, this project also ventured into the realm of fantasy and illusion. Initially, the lectures may have seemed complex and challenging to grasp, but with some effort, they could be deciphered. To facilitate this, we incorporated subtitles for segments of the videos that were screened, essentially translating the jargon-laden language from English to a more accessible form of English. This ensured that the audience remained engaged with the discussions of everyday life, as presented by these industry visionaries.

How does the use of humor contribute to your exploration of contemporary life, media culture, and art?

I believe humor often emerges when one is uncertain about where to place something, catching us by surprise. In this way, it beautifully aligns with art, as art should also be surprising and thought-provoking.

Humor often operates within hierarchies, with many jokes poking fun at power dynamics or undermining established systems. In this sense, humor can be a last line of defense, a way to find laughter when there’s little else to enjoy. It can be a way to cope with life’s absurdities, like saying, “Okay, samurai, you’re dressed so elegantly; just go ahead and end it all.” Humor challenges the boundaries of ourselves and our behaviors. Much of good humor tiptoes on the line of inappropriateness or political incorrectness, addressing issues we’d like to break down and discuss. Humor has historically been a means of critiquing society, often representing a counter-culture to conventional behavior. It also fosters social interaction, as shared laughter creates bonds. Laughing at something that defies explanation, something utterly ridiculous and absurd, is a unique and beautiful experience.

However, humor is also an inadvertent element in my work. I don’t intentionally strive to be humorous or create jokes; it’s simply the way I work. By transplanting elements from different systems into unexpected contexts, it may appear humorous, but there’s often a deeper seriousness to it.

For instance, in a recent work I created for the Cuenca Biennale called Smell Maneuver, I collaborated with a specialist to develop 18 new perfumes, each named after terms related to the biennale’s curatorial concept, such as conspiracy theory, corruption, plagiarism, and justice. Eighteen police officers each wore a different one of these perfumes alongside their standard uniforms. They were instructed to form two groups and simulate a military encounter. Instead of combat, they began to smell each other’s necks and recall the scents they had memorized. It might seem amusing that two real police officers would engage in such an activity, but I find it quite touching and sincere. Those who work in the police or military often have to set aside their individuality to represent authority and order. In this artwork, they allow themselves to become flexible again, navigating the intricate world of perfumes. They must rely on their instinctual and subtle senses, showing that people entrusted with upholding society’s laws are willing to participate in art. They were open to challenging themselves and responding to new demands, finding themselves in a situation where their roles, such as protecting democracy and combating corruption, were approached in a completely unconventional manner. To devote themselves to an artwork in this way isn’t merely funny; I believe it’s remarkable and courageous, particularly considering the current political climate in Ecuador.

Heavy Weight History delves into the weight of history through the sport of weightlifting. What was the inspiration behind this unique concept?

This project, which involved Olympic weightlifters lifting monuments in public spaces in Warsaw, was born from the connection between two neighboring countries: Germany, where I grew up, and Poland, a nation deeply affected by the aftermath of the Second World War, which left its capital city in ruins. I couldn’t help but notice that many of the public sculptures I encountered served as a way to address the collective traumatic experiences of the city. During one of my visits, I came across a sculpture depicting the German Chancellor Willy Brandt kneeling before the memorial of the Jewish Ghetto uprising. This simple act of changing one’s posture and perspective in front of something of such profound significance struck me deeply. It led me to contemplate the idea of altering the perspective of other monuments as well. I pondered extensively on the impact of war and how we might reactivate these statues in the hope of inspiring new creative ways to heal and cope with the past.

I reflected on how we elevate individuals to celebrate their achievements and the immense effort it would require to lift these bronze and stone sculptures. I also questioned whether it was even feasible and what it would signify to reanimate something static, not just in a metaphorical sense.

By collaborating with Olympic weightlifters, we transformed weightlifting—a traditionally individualistic sport—into a team endeavor and, in a way, pioneered a new sport. This project provided an opportunity to revisit the various circumstances and ideas that these monuments embody in the city, ranging from Seejungfur, the mythical symbol of Warsaw, to Ronald Reagan, a statue of a strong man, and the statue of sleeping soldiers, featuring two Russian and two Polish soldiers side by side, representing the many who lost their lives.

Your work frequently challenges established norms and perceptions. What guidance can you offer to aspiring artists aiming to push boundaries in their artistic endeavors?

I believe that performance art serves as an excellent platform for emerging artists. The medium of performance provides immediate feedback from the audience, enabling you to observe the reactions and responses of your viewers. This one-on-one interaction allows for personal growth and self-reflection right from the start. In the course of history, you can observe many instances where artists began with performance and then expanded into other artistic forms.

Additionally, don’t hesitate to take some risks and experiment with different mediums. Embrace the opportunity to explore various artistic avenues, as you may discover a medium that allows you to express yourself more freely. Let go of the pursuit of perfection, and instead, confront your fears and see where they lead you.

Are there any upcoming projects or themes you’re excited to explore in your future work?

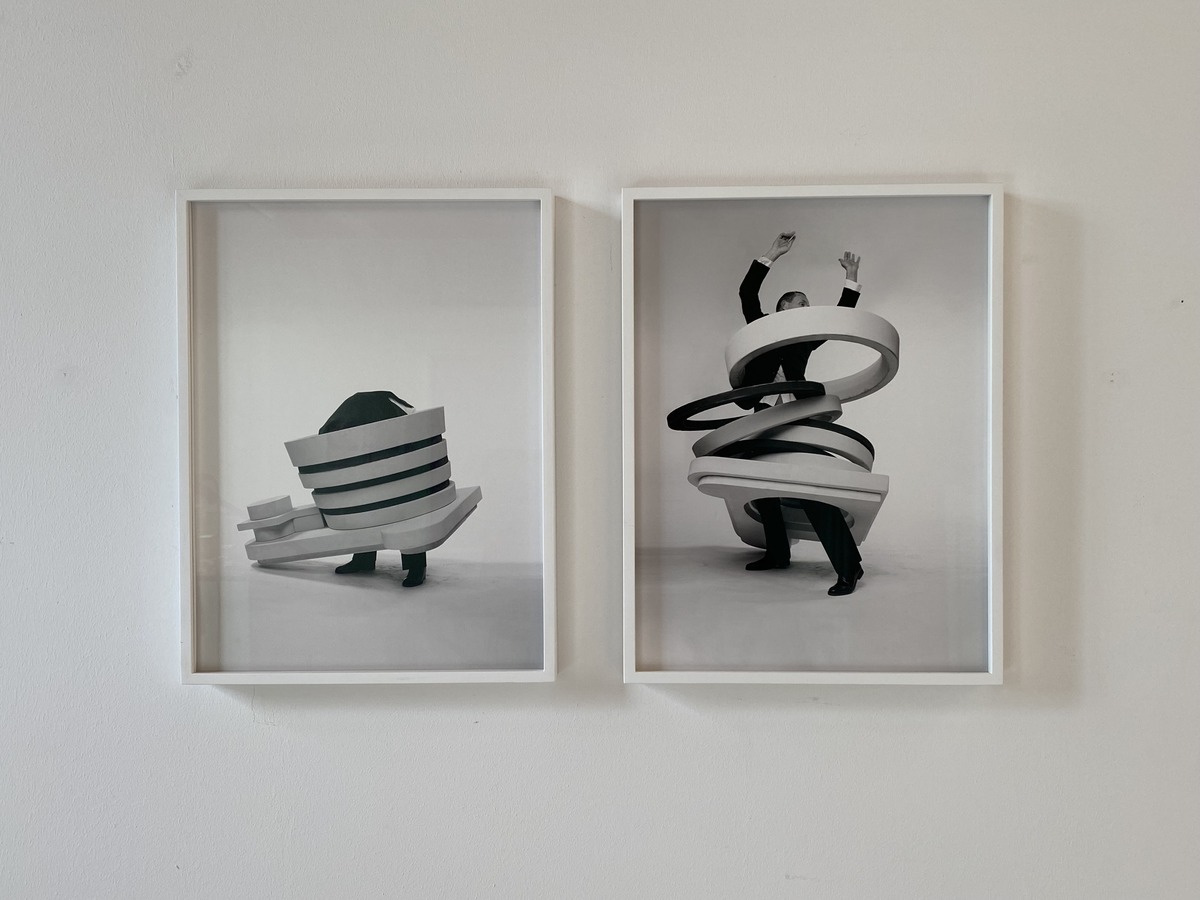

I’m thrilled about my current project, which I’m calling Geknetete Stadt. We are still searching for an appropriate English title for it. This project has been a captivating exploration of different generations and the intergenerational elements it embodies. I find it especially fascinating to observe the thoughts and ideas of 8-year-olds–they are truly remarkable! I mean, the concept of creating a self-portrait as a bin–how can you top that? Or a cabinet designed to display amusing phrases!

This project was a collaborative effort with a group of schoolchildren, for whom I conducted a workshop in their city. During the workshop, we roamed the city streets, pretending to be various objects commonly found there. The children eagerly embraced this exercise, envisioning themselves as objects such as trash cans, letterboxes, and lamp posts, which they then imitated while we documented their actions through photography. Upon returning, we engaged in discussions about the significance of these objects and what they symbolized. One girl, for instance, described herself as a chair for those who needed a moment of rest, while another suggested a letterbox containing medicine that could extend a person’s life by 20 years. Even the child who chose to portray themselves as a trashcan prompted us to reflect on how one generation leaves behind “trash” for the next to clean up. It’s truly remarkable how seemingly straightforward statements from these children, when translated into sculpture, evolve into rich and thought-provoking ideas.

In the second phase of the workshop, following the photography session, I encouraged the children to use clay to create physical self-portraits. These clay sculptures are now being transformed into life-sized metal sculptures with a protective lacquer coating, which will once again be displayed in public spaces.

Photo credit: © Christian Jankowski studio

Editor: Kristen Evangelista

More images: