Artist’s Statement

My work

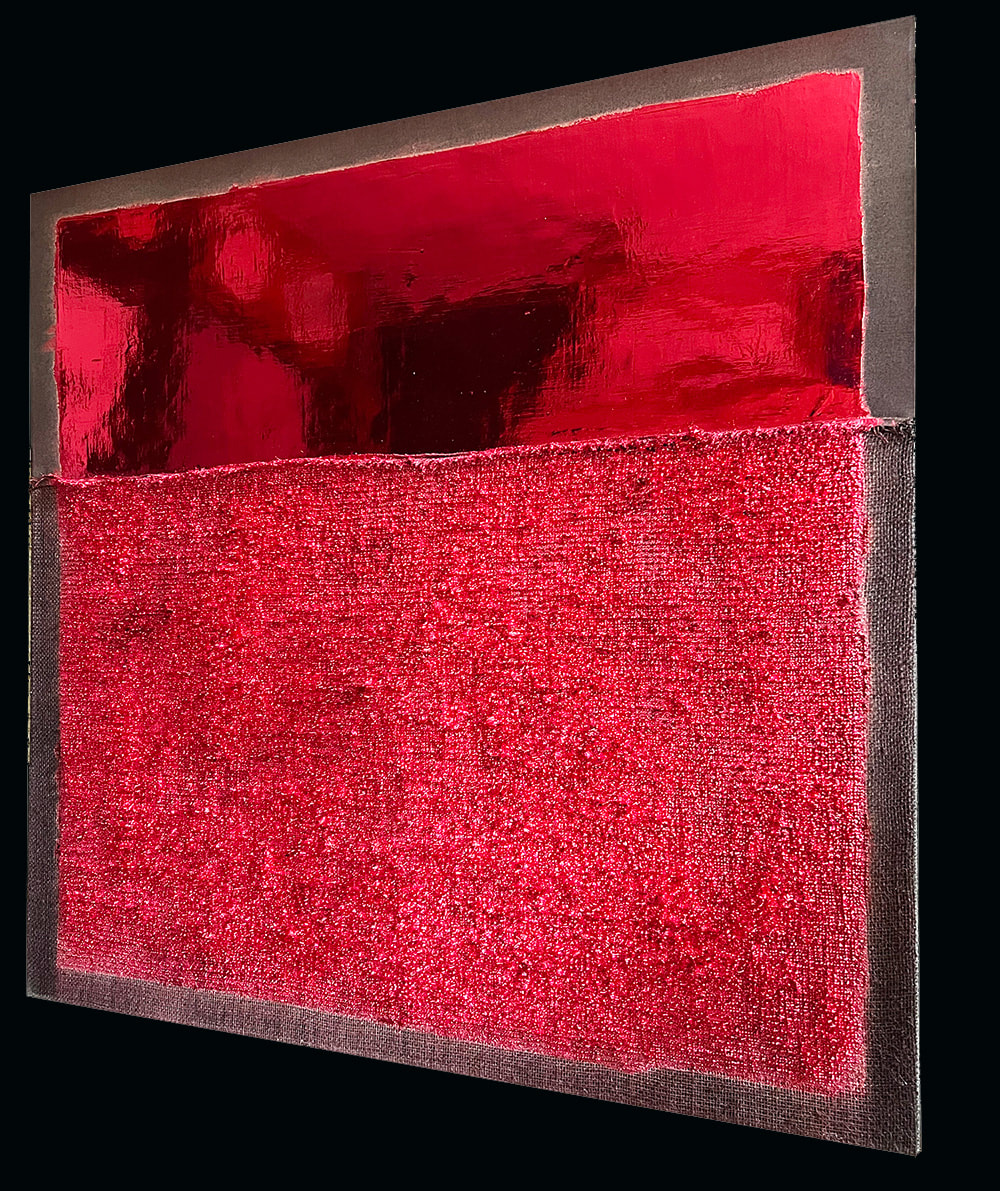

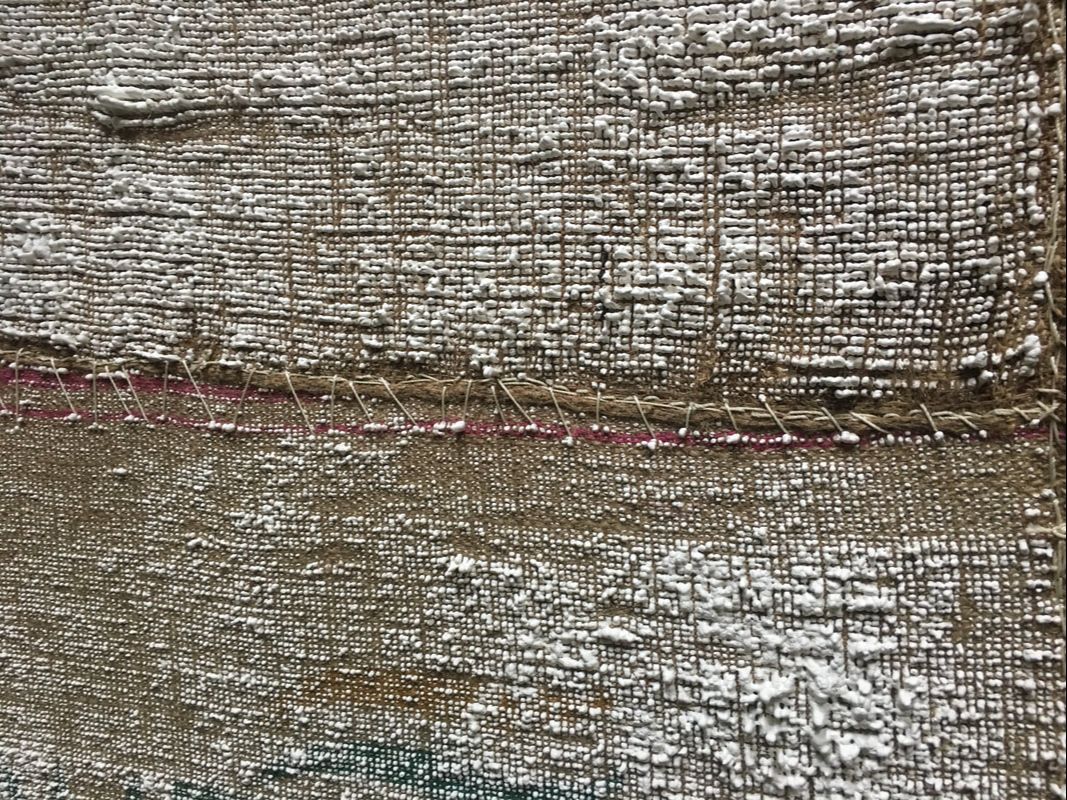

I am inspired by materials–items that seem to have lost their purpose and identity. In fact, I believe that materials have their own journeys, moving from one place to another. At each step, they lose something in their passage as they seem to be falling apart, then gaining as I sit at the back of a church or a synagogue, hand stitching many of the rips and “sores” in the material into a canvas for my work.

For me, this is especially true for jute sacks, and the memory of what was “inside” and “outside.” They speak to me, forcing me to question renewal, value, migration, globalization, and economic exchange. The sacks that I gather from farmers markets and take new life as part of my artwork conjure many memories and become the signifiers of exploitation and abuse as well as beauty and the creative force.

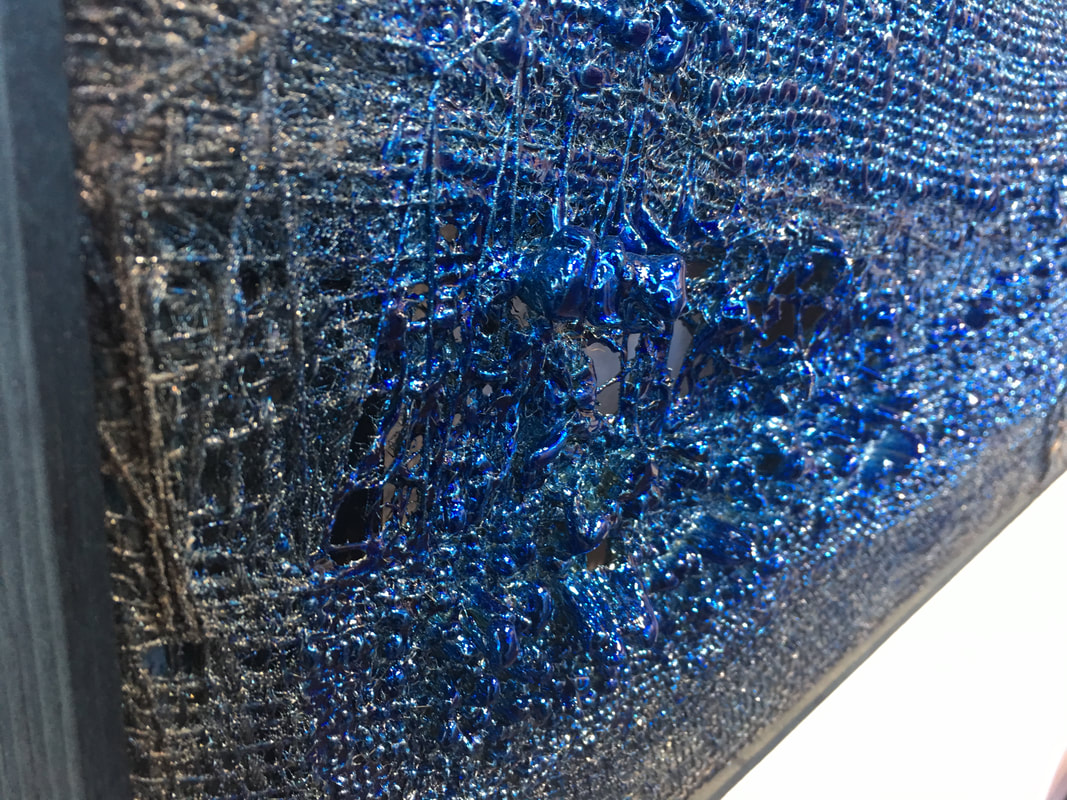

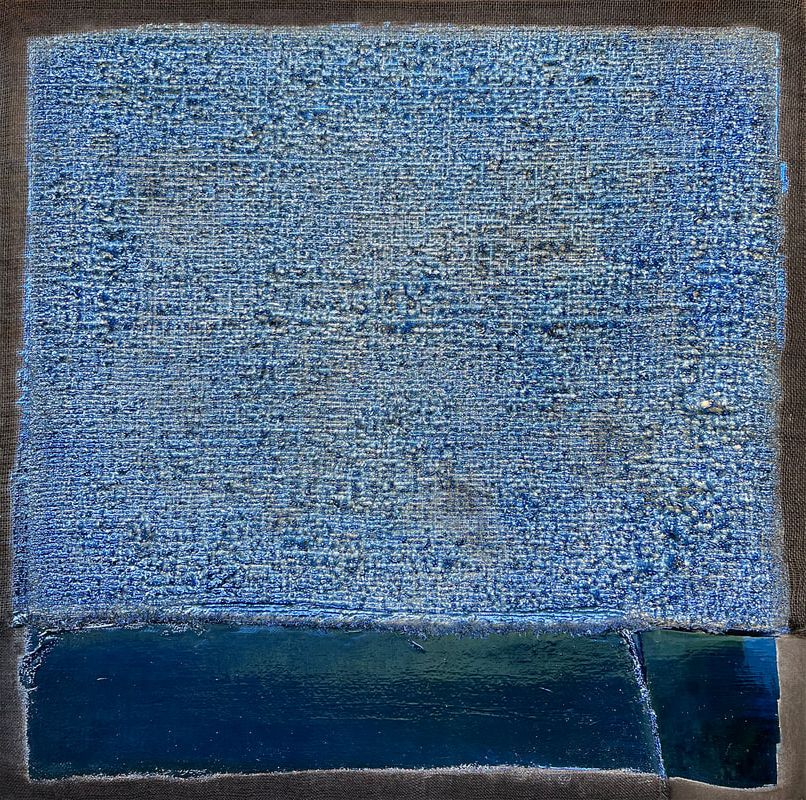

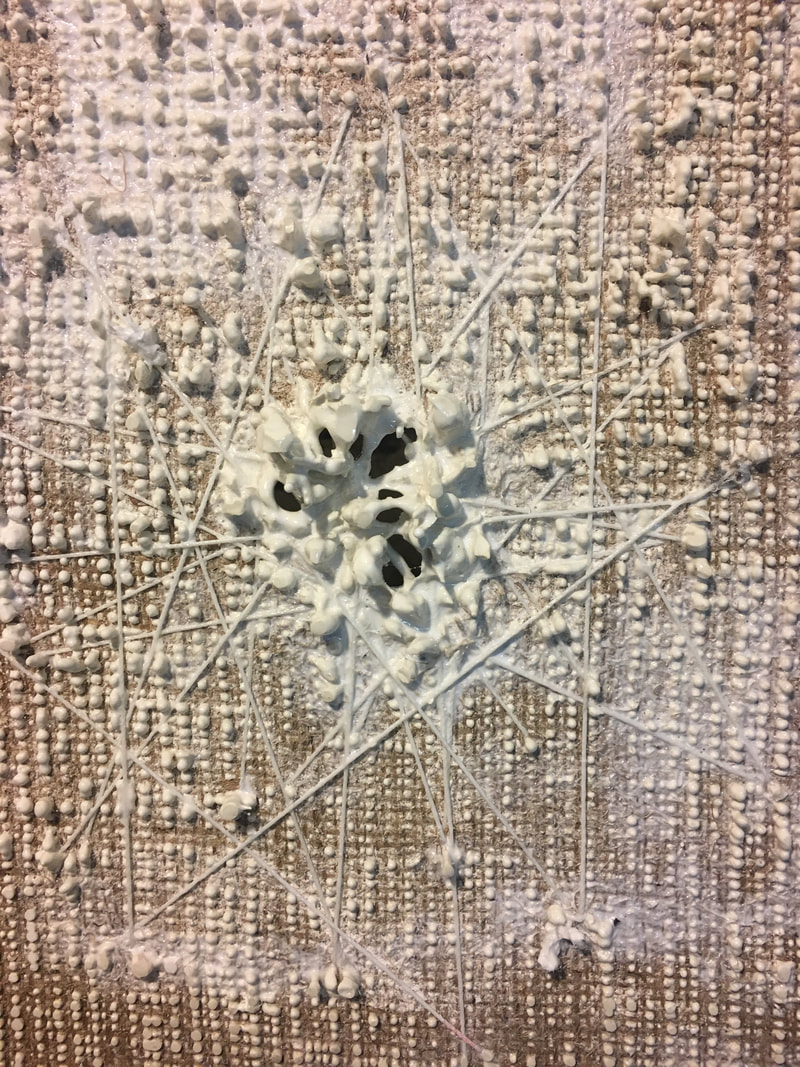

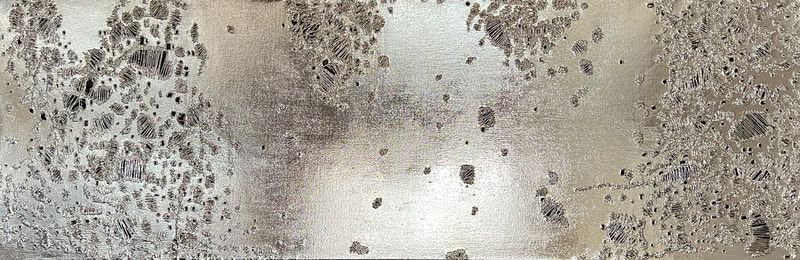

As I weave plaster, crushed pearls, resins and precious metals into them, the sacks are transformed with new life. Architecture, entropy and socio-dichotomies are “built” together as light, shadows and an infinity of scintillations emerge to unveil a new language and expression.

My past

As an eight-year-old boy, I remember vividly my grandfather taking me by the hand to the Gold Museum in Bogotá, Colombia. It was the most incredible thing I had ever seen. How I remember the sparks, the glitter and reflection. How magical!

I remember to this day when we sat in a dark circular room in the museum. I was holding my grandfather’s hand tightly. Suddenly, the light in the room started coming on, second by second, and everything started sparkling, glittering, shining!

I was startled by what I had just experienced: It was a visceral reaction of fear, visual feast, and magic! When all the lights were fully on, I felt as if was inside the sun. That memory is the seed of my work, the nugget of my creative endeavors.

Later as an immigrant, with many “dents” and setbacks along the way, I held on to that “golden light.” This spark led me to study art and architecture and develop a practice that allows me to see the light in a simple jute sack.

Source https://www.eduardoterranova.com/index.html/

Interview

Artist: Eduardo Terranova

By Carol Real

You moved to the United States from Colombia as a teenager. How did this transition impact your adolescence?

Coming to the United States wasn’t a big shock for me, despite the differences in language and culture, because most Latin American countries have been so influenced by American music, styles, and fashion. As kids, we all dreamt of speaking English but learned the language through American pop songs, which we sang even if we did not understand the lyrics.

Later, once I was here and exposed to American culture, art, and the English language, my mind began changing and soaking up everything around me. I wasn’t creating “my new world,” but I was adding to what was already there much earlier in my life.

In particular, there were illustrations I discovered by “illegally” entering my grandfather’s private library, which was hidden in a closet where no one was allowed. I was six years old when I found the door ajar and viewed big, heavy books. I opened the closest ones, eagerly turning the pages. The bold imagery kept me so engaged and excited. It was not until I was twelve or fourteen years old that I realized that it was Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, alongside other books with amazing graphics that scared me.

As for the different landscapes, I still miss the Andes mountains, the longest mountain range in the world. Although it’s hardly the same, I occasionally go to the Catskills here in New York to feel a little bit back home, if only just a little.

Your work is often inspired by your memory of Bogotá. Please share how your grandfather introduced you to the arts.

As an eight-year-old boy, I vividly remember my grandfather taking me by the hand to the Gold Museum in Bogotá, Colombia. It was the most incredible thing I had ever seen. How I remember the sparks, the glitter, and reflection—how magical!

To this day, I remember when we sat in a dark, circular room in the museum. I was holding my grandfather’s hand tightly. Suddenly, the light in the room started coming on, second by second, and everything started sparkling, glittering, and shining! When all the lights were fully on, I felt as if I was inside the sun.

I was startled by what I had just experienced: it was a visceral reaction of fear, a visual feast, and magic! That memory is the seed of my work—the nugget of my creative endeavors.

I became fascinated by shamanism and gold objects. The light, glitter, reflection, and magic were incredible. It was like tributary rivers flowing towards the ocean, to the source, to me! It was pure gestalt!

Later as an immigrant, with many “dents” and setbacks along the way, I held on to that “golden light.” This spark led me to study art and architecture. It also enabled me to develop a practice that sees the light in a simple jute sack, which became a key element in my work.

How and when did you develop your unique style and medium?

It’s not easy to pinpoint the exact moment or all the influences that collectively helped define my choice of medium and style.

There were the coffee bags—burlap or jute sacks where beans are stored and transported, which were familiar from my childhood. Most small coffee growers and peasants in Colombia dry coffee beans on top of these kinds of sacks. When I was flying my kites, I often saw coffee beans drying on roofs.

As kids, we loved playing with these bags, mostly for the fabric’s rough texture, grid pattern, or even for their lack of sophistication. In country cafes, the full bags served as seats for customers. I believe these influences came to me little by little, but when I began studying architecture I understood that I’ve always loved materials.

After my grandfather retired from teaching, he started a real estate business, buying and selling houses. The initial influence of my grandfather was a springboard for my practice decades later. Also, this “discovery” during school and afterward brought me back to my own country and culture.

My whole family participated in renovating the houses: adding rooms and carrying out repairs or other construction work using a variety of materials. These jobs involved painting, building walls, and working with “poor man’s materials” such as plaster, paint, bricks, cement, concrete, gravel, etc.

I believe this opened up a new world for me. It reaffirmed and confirmed my proclivity and love of art, architecture, and materials.

It could be said that your artwork is interactive. How important are light and colors in your work?

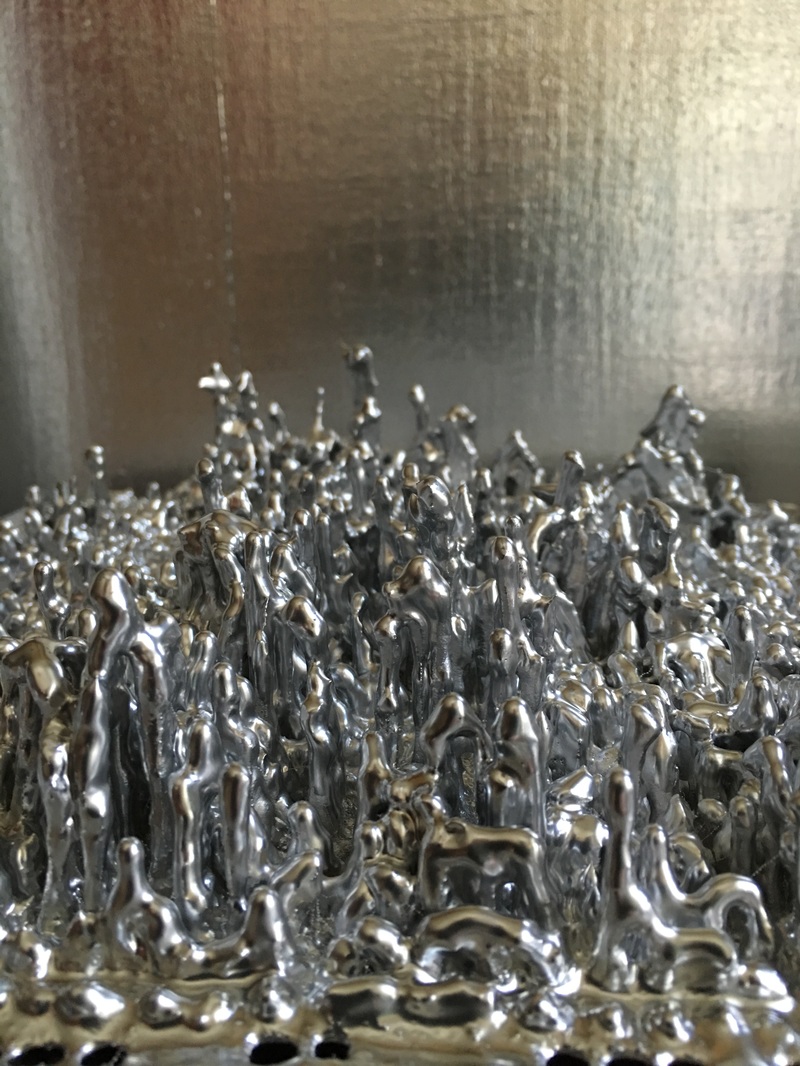

I see my works as examples of fusing many sources. They are about light but also about reflection, absorbing, and emitting light. Something that amazes me is that in the Pre-Columbian cultures, especially in Colombia, the reflection of gold was the measure of power and health. Gold was hammered from a tiny nugget to sheets of gold. Pectorals, earrings, and nose rings were the most popular.

Geographically, Colombia is in between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, also known as the equatorial zone. This means the sun shines the most at noon and is right above our heads. This is important as any metal, particularly gold, glitters and shines the most during this light.

Describe your artwork and your creative process. How long does it take to produce your artwork?

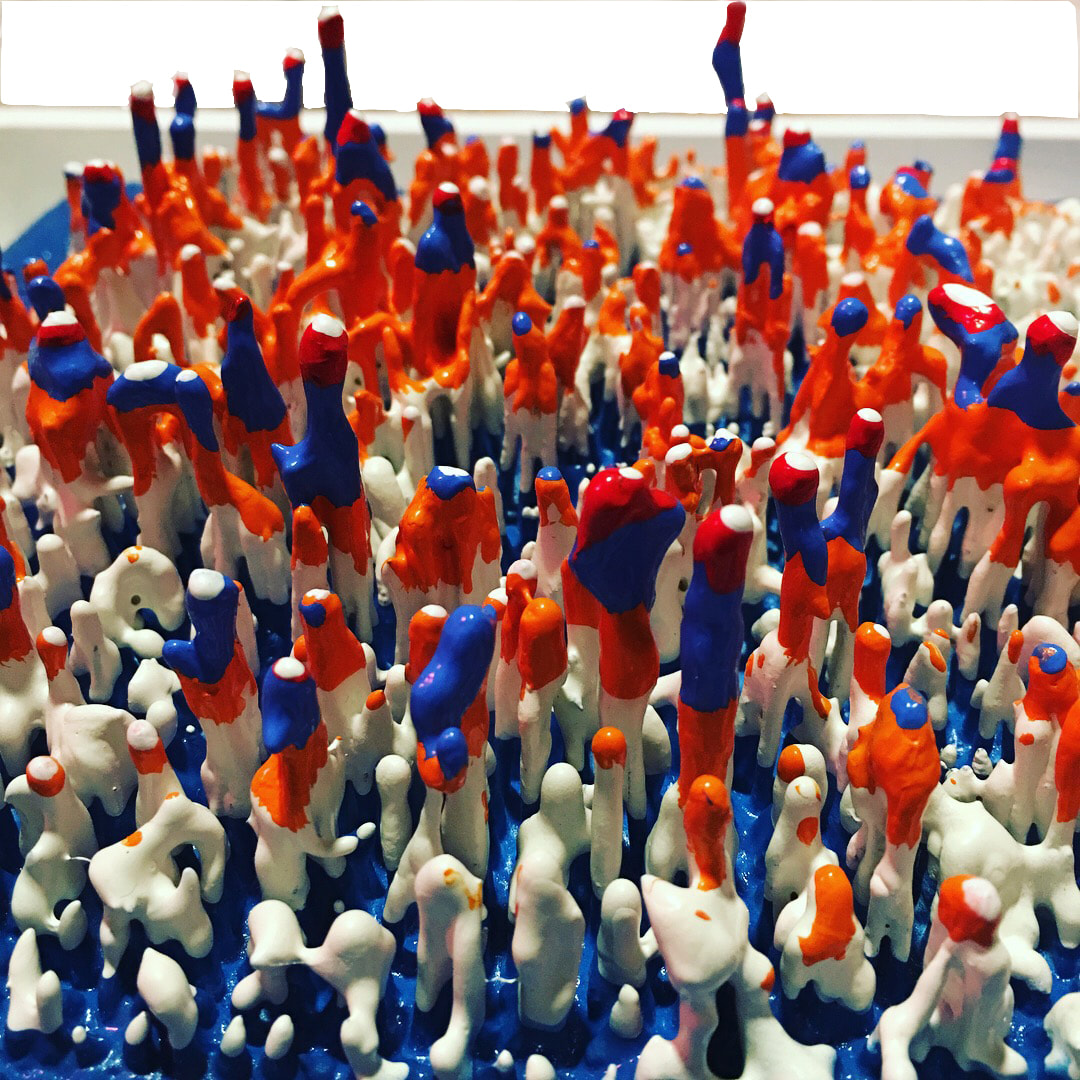

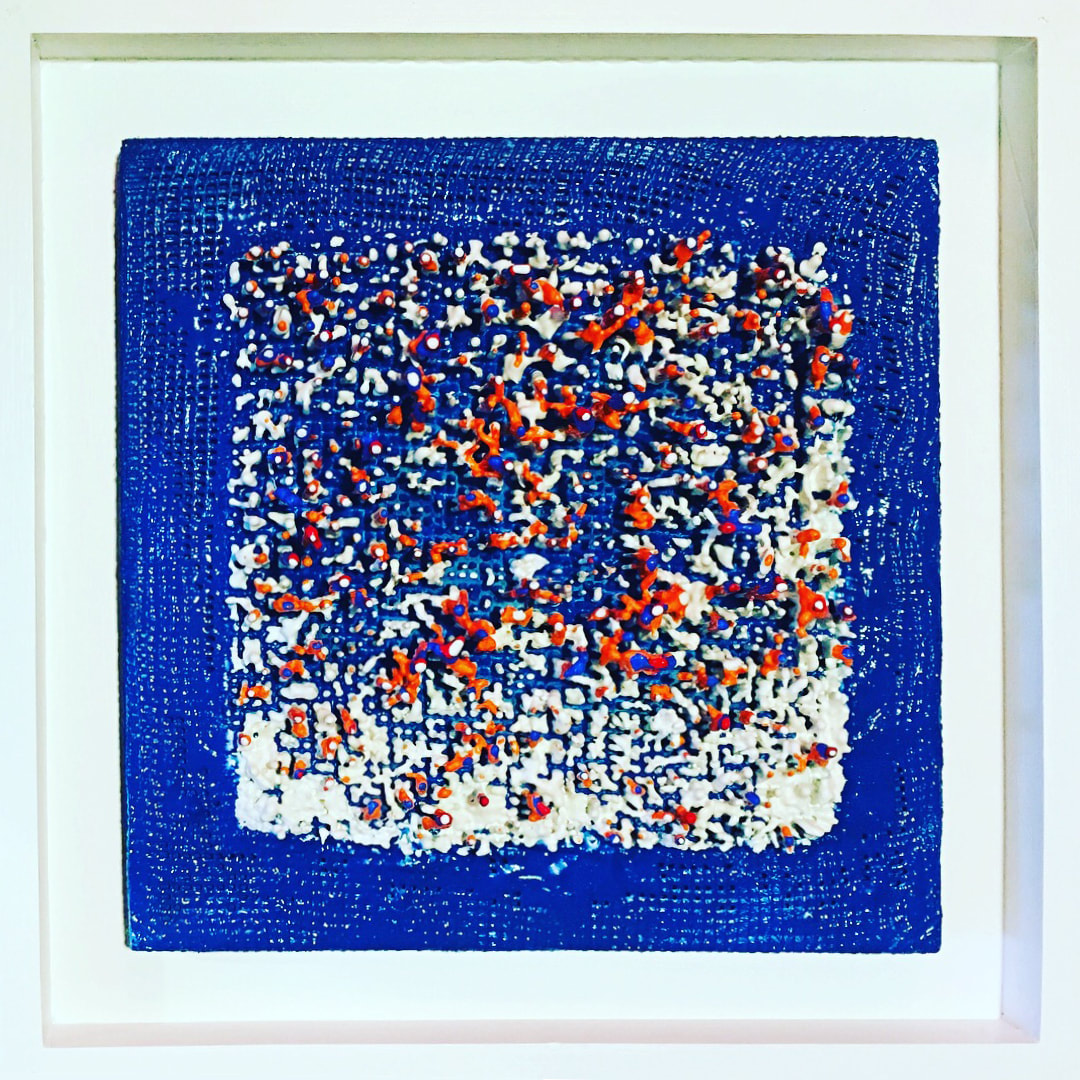

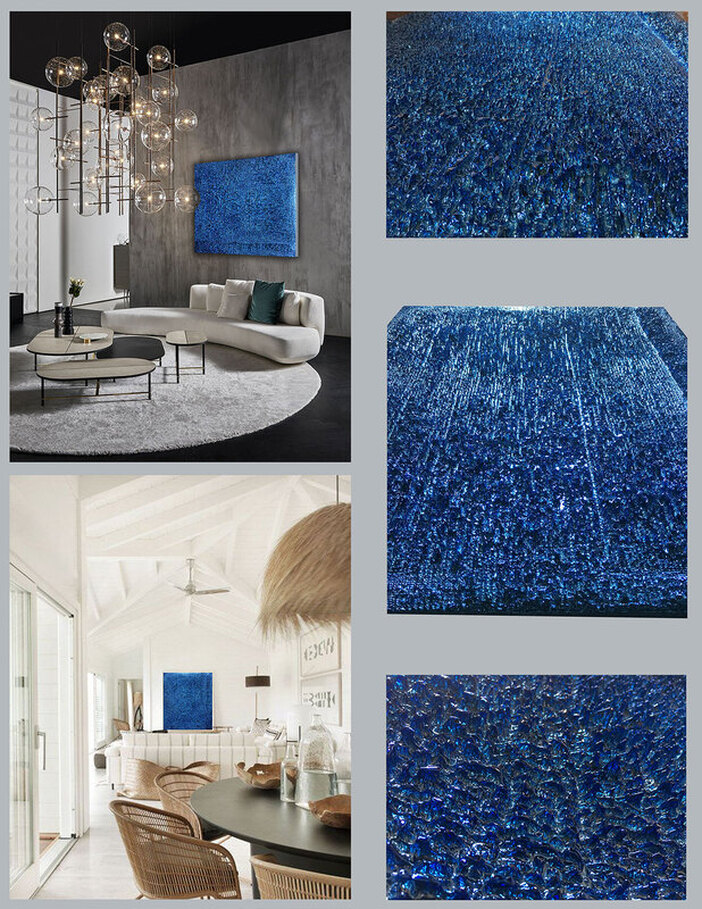

My works are about how one moves around and experiences them. Most of my paintings are monochromatic. It’s so hard to understand a single color under such visual parameters. A square inch can contain thousands of tiny scintillations. Furthermore, my works are made with thousands of plaster protrusions that extend up to four and five inches from their surface, making them three-dimensional. I can’t create flat paintings. Like architecture, they have to be “physically and visually experienced.”

I don’t have a particular amount of time or time frame that a work might take. Size, of course, dictates time and complexity. Also, it depends on the availability of materials. I gather fabric or jute sacks from farmers markets: either at Union Square farmers market in NYC, in my neighborhood on 82nd Street and First Avenue, or upstate New York.

Other times, I destroy fabric canvas using gouges and metal brushes; I then reconstruct that destruction by hand-stitching. I consider this process therapeutic and meditative in nature. I see it as “emotional reparation,” allowing me to keep things together. The process of hand stitching takes months and months, using miles and miles of thread. Yes, there are tears, poked fingers, and lots of blood. I see myself sometimes as being attached to my umbilical cord.

I’m very much fond of this work as it is the most solitary. It’s psychologically peaceful and turbulent at the same time. My mind drifts, remembers, and forgets all under my breathing while my needle and thread go in and out creating complicated patterns and moments that the painting will never reveal.

How do you explain your unique works that combine the luxury of metals and humble materials, making an analogy to the immigrant experience?

Well, only some things are so cerebral. Once the stitching is done or the plasterwork has hardened, the fun starts with the plating techniques that I use to coat the surface of my work. Here is where I reconnect with and conjure my ancestors. Yes, those gold pieces are full of light, glitter, and magic. The magic that connects the celestial, terrestrial, and underworld. It’s the interconnections that attract me most.

I don’t pretend to be a shaman but through my works, the “spark” is still alive as faint as a star and bright as the sun. What amazes me is that such humble materials as jute or burlap sacks or plaster can be transformed through my unique process into “luxury paintings.” The reader may be thinking of “Arte Povera” but the reality is that every single material is charged with such energy, all compressed and waiting to be released. For me, materials have their journeys, their own mind per se. I can’t help but think and understand that my journey as an immigrant and the material’s journey are universal themes.

I think of the burlap sack as analogous to immigrants, arriving with empty pockets, broken, abused, and exploited. Nevertheless, there is always a light at the end of the “sack” and this is where the metal finishing on my works glitters, reflects, absorbs, and gives light and life to the viewers.

Can you recall any public reactions to your artwork?

Yes, “How the hell did you make that?” and “I feel so energized in the presence of your works.”

Is there something that you have not done yet and would like to accomplish in the future?

Yes, I would love to start a series of large sculptures inspired by the protrusions and three-dimensionality of my works. This requires 3D scanning and 3D printing. Right now, it’s an expensive process. Perhaps one day.

Favorite quote

“If I had more time I would had written a shorter letter”

I understand this quote as a compression of time and action:

-

How do you compress suffering?

-

How do you compress a journey?

-

How do you compress trauma?

-

How do you compress tears and time?

-

How do you compress love?

We are so connected to the cosmos. We are made out of stars and galaxies; we are so connected with time and space and yet we are so ephemeral. We are celestial winds.

The earliest recorded use of the quote, “If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter,” comes from French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal’s 1657 work, Lettres Provinciales. In French, the quote reads, “Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que je n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte.” This translates to “I have made this longer than usual because I have not had time to make it shorter.”

Editor: Kristen Evangelista