Interview with Renelle White Buffalo-

How did you get started in arts? Who were your early mentors?

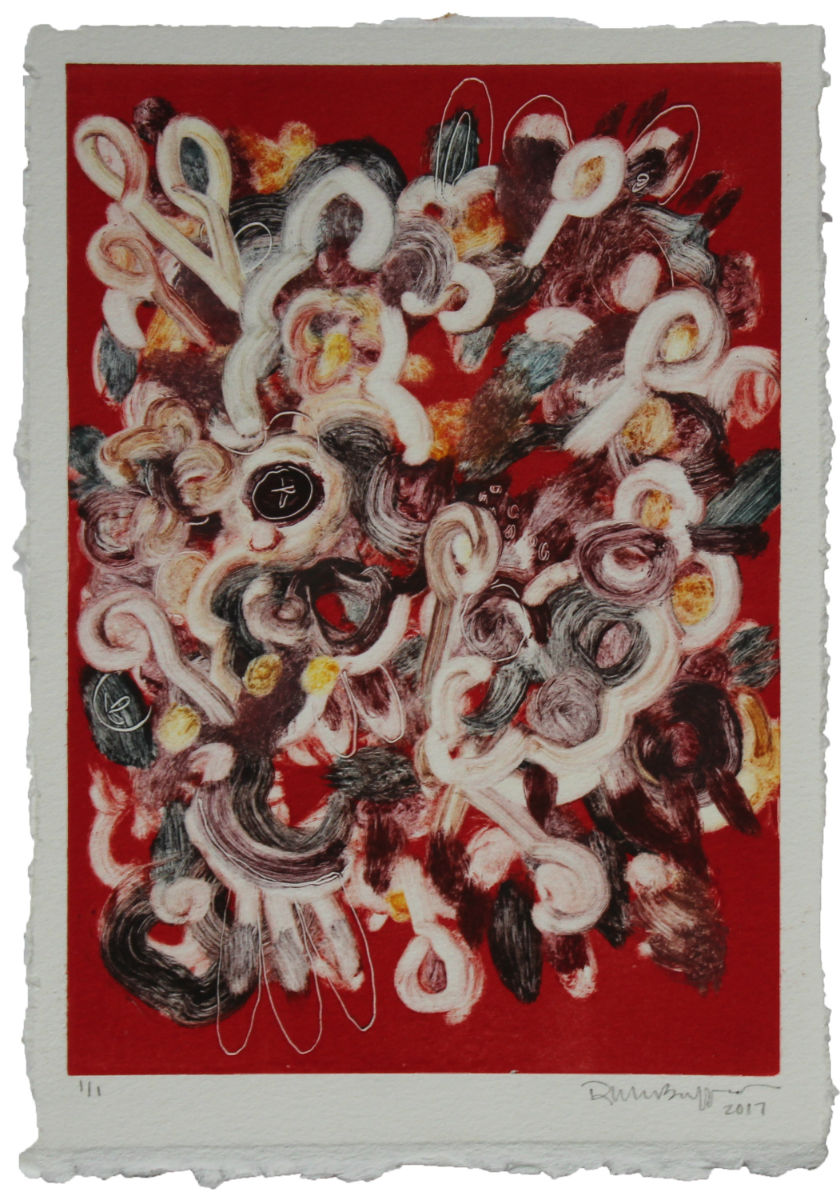

I would constantly ask my grandma to draw for me, and we eventually started to draw together. She taught me to use it as an outlet, which became a protection for both of us. Art became my passion, and I knew it would eventually enable me to leave the reservation and move to a big city. I was lucky to have Mr. John LeBouef as my art teacher from elementary school through high school. He influenced me to go to college and major in fine art. After college, I moved to Los Angeles where I started to work on art that reflected my culture—and me. I began to use acrylic paint, and met many indigenous artists such as Ernesto Yerena Montejano and Vyal Reyes. I also had the honor to work with master printmakers like Jose Alpuche and the late Richard Duardo. When I switched from the west to the east coast, I met Marc Dennis, who often reminds me of the unique voice I have. He recognizes the ambitions and motivations behind my paintings.

How was your childhood on the reservation?

These perceptions of Native art are damaging. They allow the American genocide to continue. They don’t allow for acknowledgement of Natives in present day society, let alone in the contemporary art world. I knew this was an issue long before I started my career as an artist. At one point, it made me hesitant to acknowledge myself as a Native American artist. Even the Native artists that I grew up admiring are not fully recognized in the contemporary art world. It made me believe that I either had to be a Native American artist or abandon everything Native American about my art. Now, when I create, I aim to abolish limited perceptions about what Native art really is.

It was an honor to have such a personal show in my home state. Even though my work had appeared there in a group show, the solo exhibit (curated by CAIRNS, Center of American Indians Research and Native Studies) was especially welcome, as I had been artistically unmotivated about painting during the prior year. This was an opportunity to re-focus and explore more deeply my personal background. As a child I loved that museum, and I had set a goal of showing my work there someday.

What is the most rewarding thing about your work?

It is that I am doing it. I am making my art and my culture my life. It constantly challenges me and shows me what I am capable of. It gives me a reason to converse about my culture, and share why that culture means so much to me. It’s also gratifying to see my impact on students-after a class, for example-or when they tell me about the reports they are doing on my art. I’m not sure I deserve it, but I am grateful to feel that I am giving back to my community and to South Dakota. I try to live up to the task, and I hope to be able to shift our national perspective on what being Native is.

What are you doing when you’re not creating? What hobbies do you have?

I enjoy watching art documentaries, studying the Lakota language, and reading books by Sherman Alexie or books about other artists and entrepreneurs. I am always learning more about SEO tactics, social media strategies, and how to become more productive with my time away from painting. I discover artists through Instagram, attend art openings and museum exhibits, travel, and become immersed in virtual reality.

In my studio space, I have photos of my grandma and of my favorite art. They are a direct source of inspiration. I also have photos of my great grandparents, paintings that my great-grandfather created, some swatches of colors that I have used in past paintings, and some flowers I love.

In addition to galleries and museums and walking around the city, I love the NY Botanical Garden and visiting family in New Jersey.

Finally, can you tell us something about your latest projects? What are your plans for the near future?

In April, I will be speaking and working with some of the students at Northern State University in Aberdeen, South Dakota.

My plan is to visualize and incorporate paths and people who have traveled them. I want to find more colors that are found in nature, particularly those at some of our sacred sites. I intend to do some larger scale work on canvas, do printmaking, and explore mediums such as oil paint and sculpture. I am reworking my website, and I plan to have it translated into the Lakota language. I plan to constantly learn and adapt.