Bio source https://tobiarava.com/biografia/

Interview

Artist: Tobia Ravà

How would you describe the beginning of your art career? What was the best and worst career advice you received?

My career as an artist stemmed from watching my father—an engineer—work on his drawing board with his drafting machine and parallelograph. Then, in the seventies, Linus arrived in Italy with Charles Schulz’s stories of Snoopy who flew on his doghouse against the Red Baron’s tri-plane. I drew this on the wallpaper of my bedroom at my grandparents’ house.

The best piece of advice I received again came from my father who told me to keep working at my drawings and not to throw them away even if I didn’t like them straight away. The worst piece of advice was from my maternal grandfather who instead wanted me to throw away my paper and crayons and go to work in a factory— his factory—where he produced felt to make paper.

Your style is very unique and distinctive, combining numbers and letters in Hebrew. What is your inspiration for this creative approach?

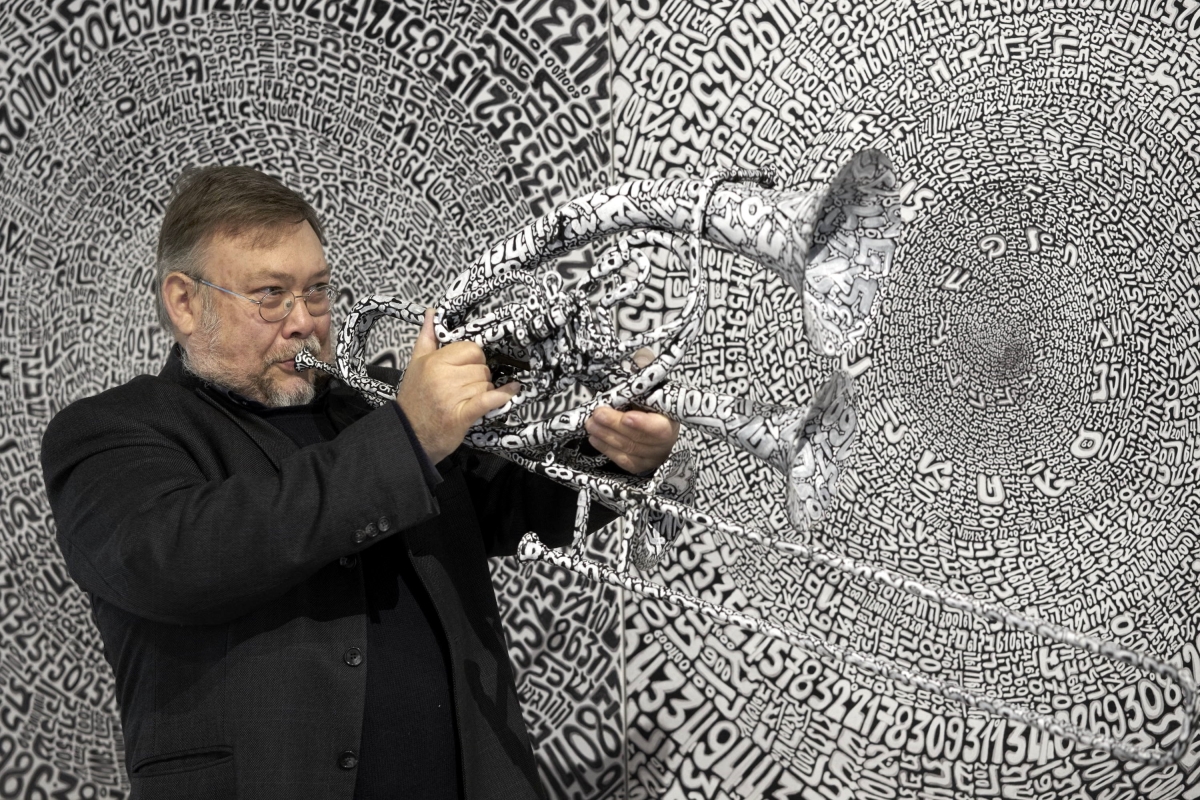

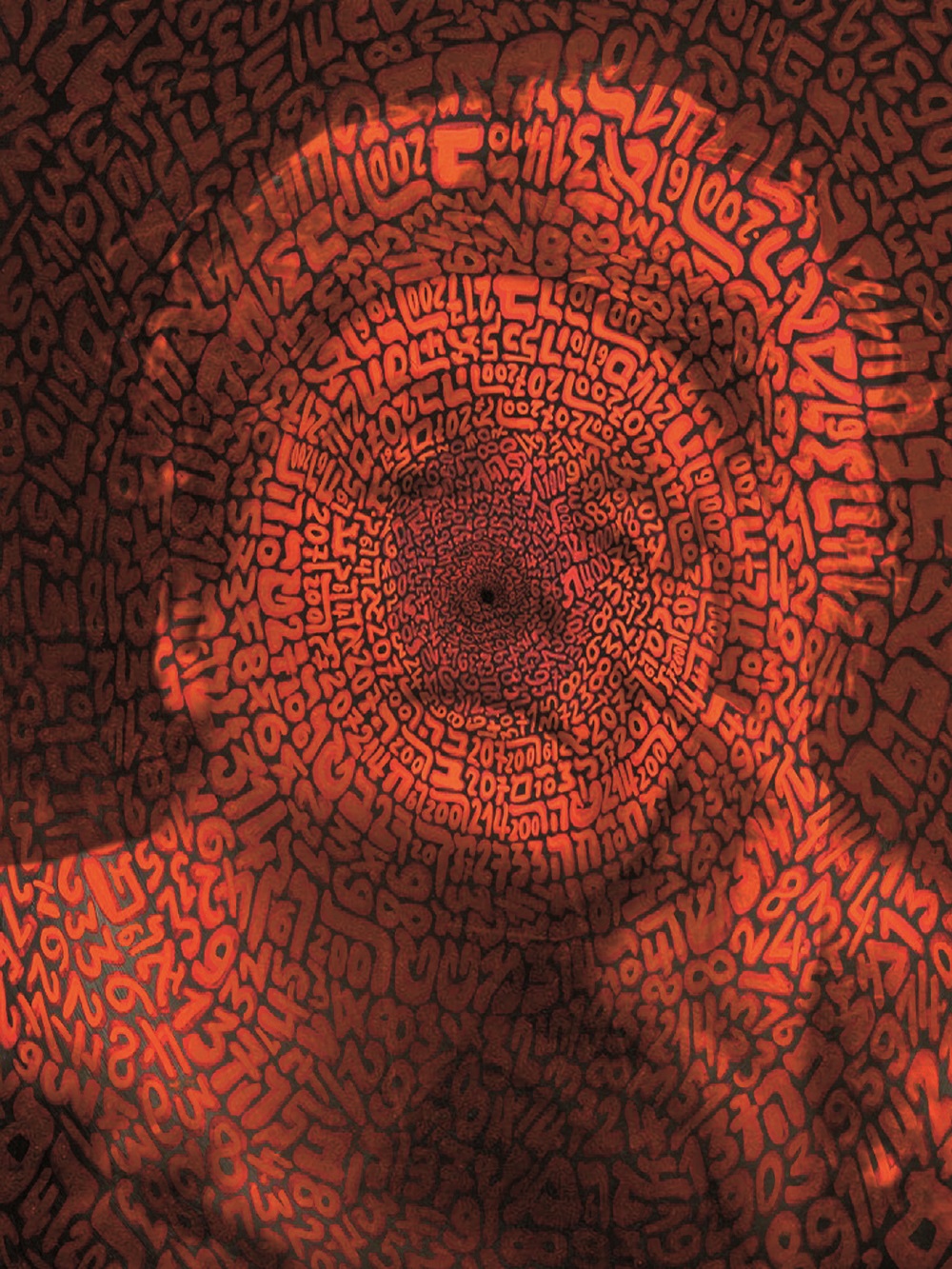

At Bologna University, where I studied Art Semiology, I was a student of Umberto Eco. He steered me towards studying the Lurian Kabbalah, after which I quickly went on to study Gematria (a system of assigning numbers to letters). I already painted using letters of the alphabet and Greek and Latin words; then, I began to use numbers and Hebrew letters.

Today many artists turn to technology to make art. How would you describe your conventional techniques and careful arrangement of symbols and numbers to form a perfect image?

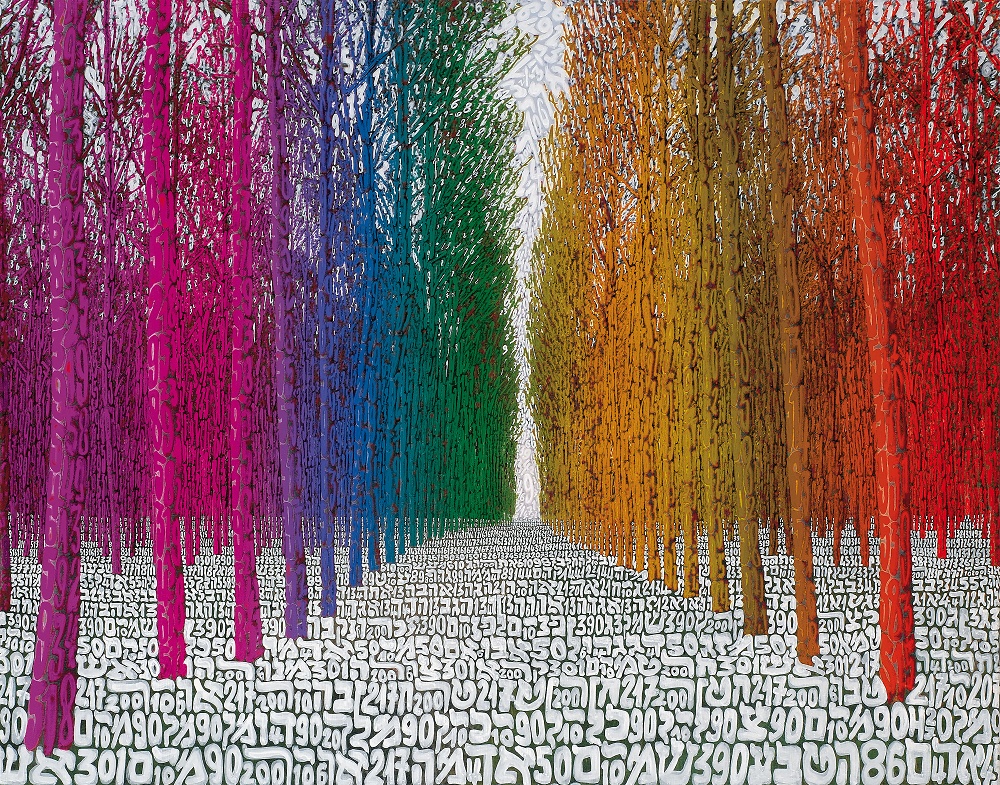

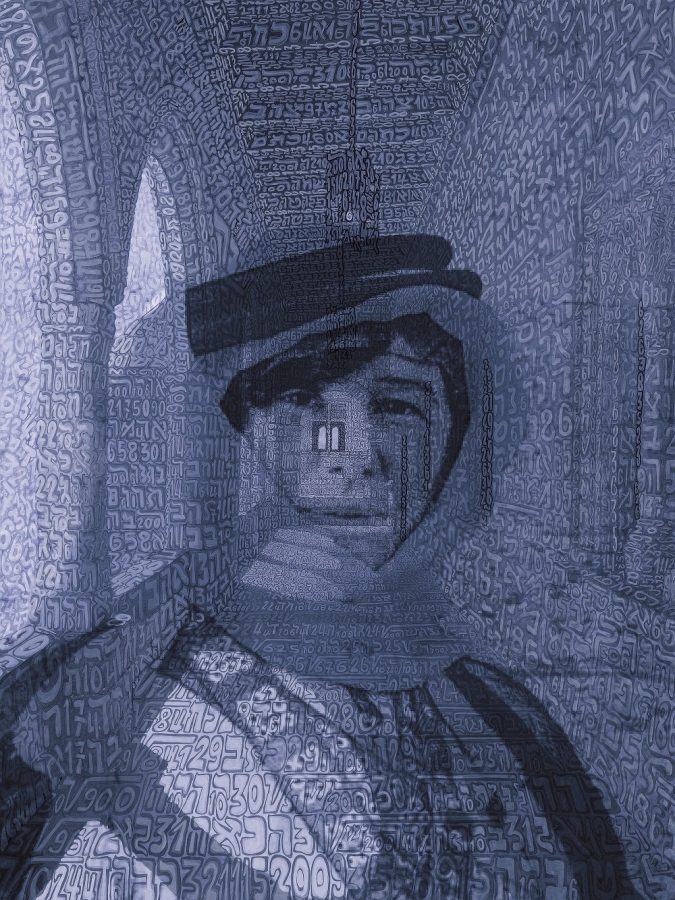

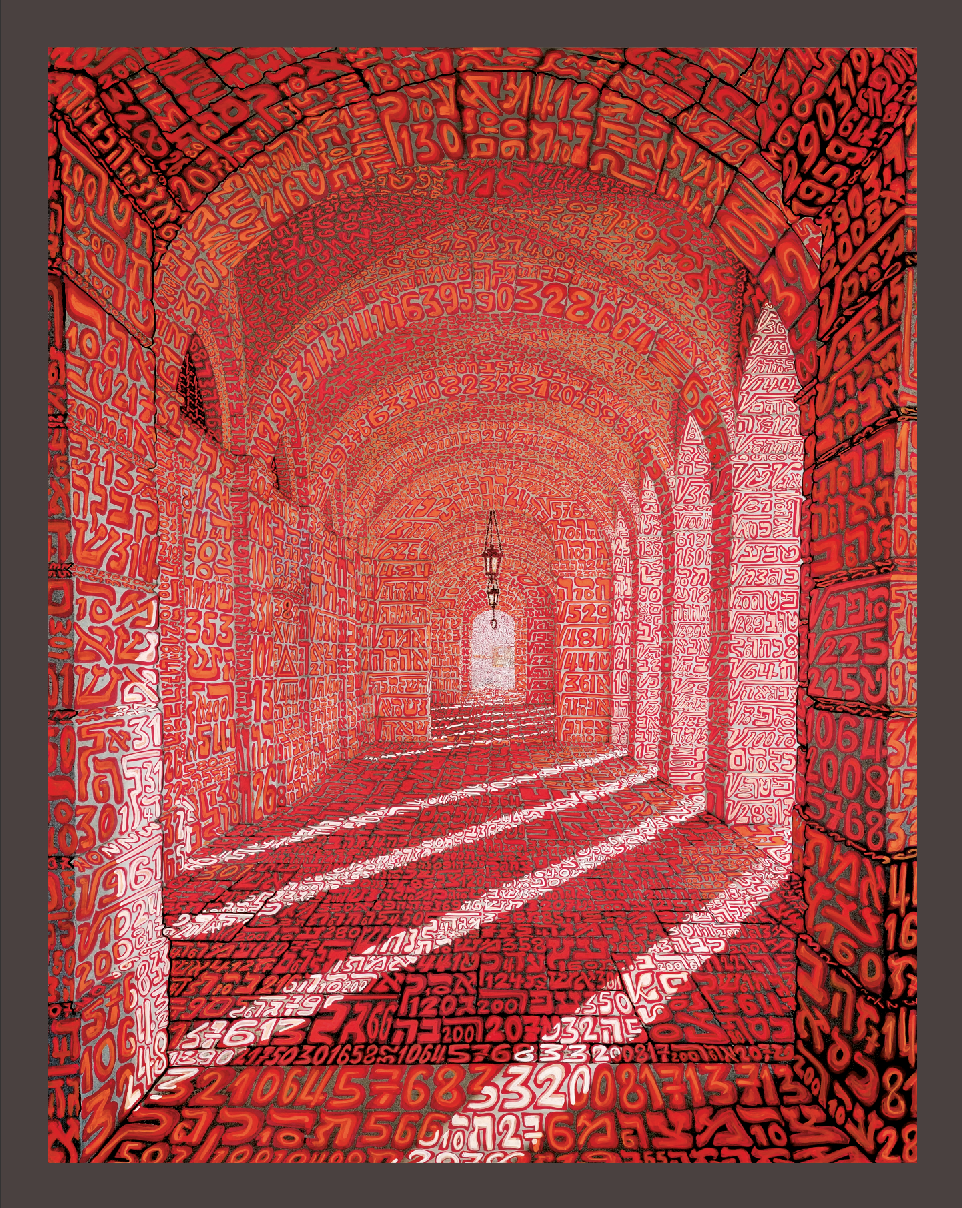

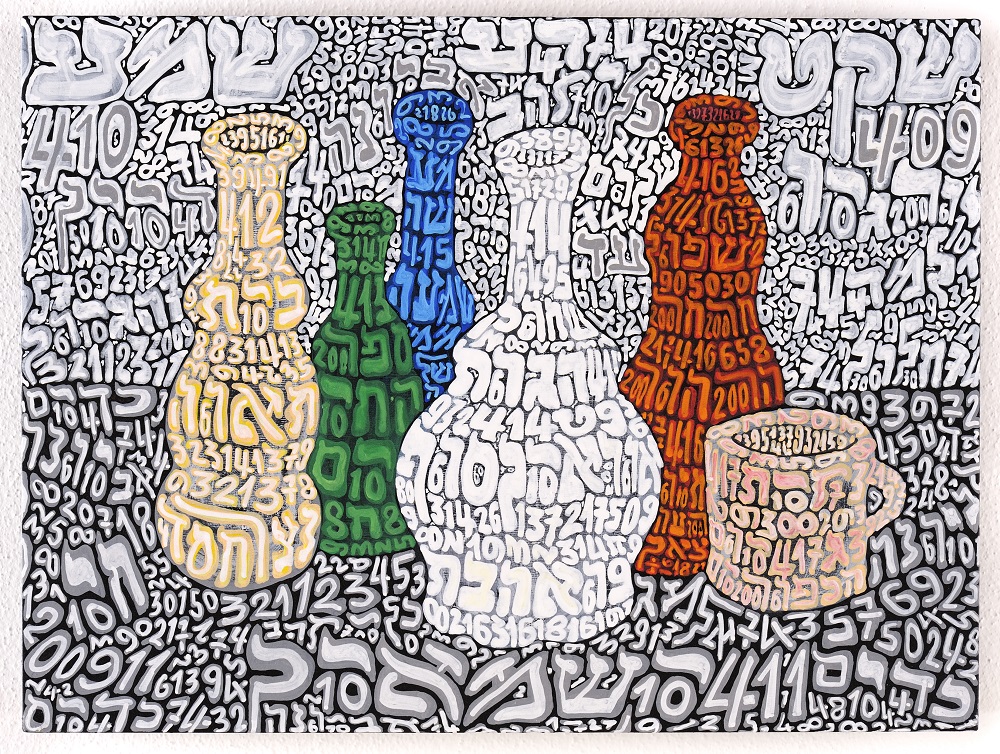

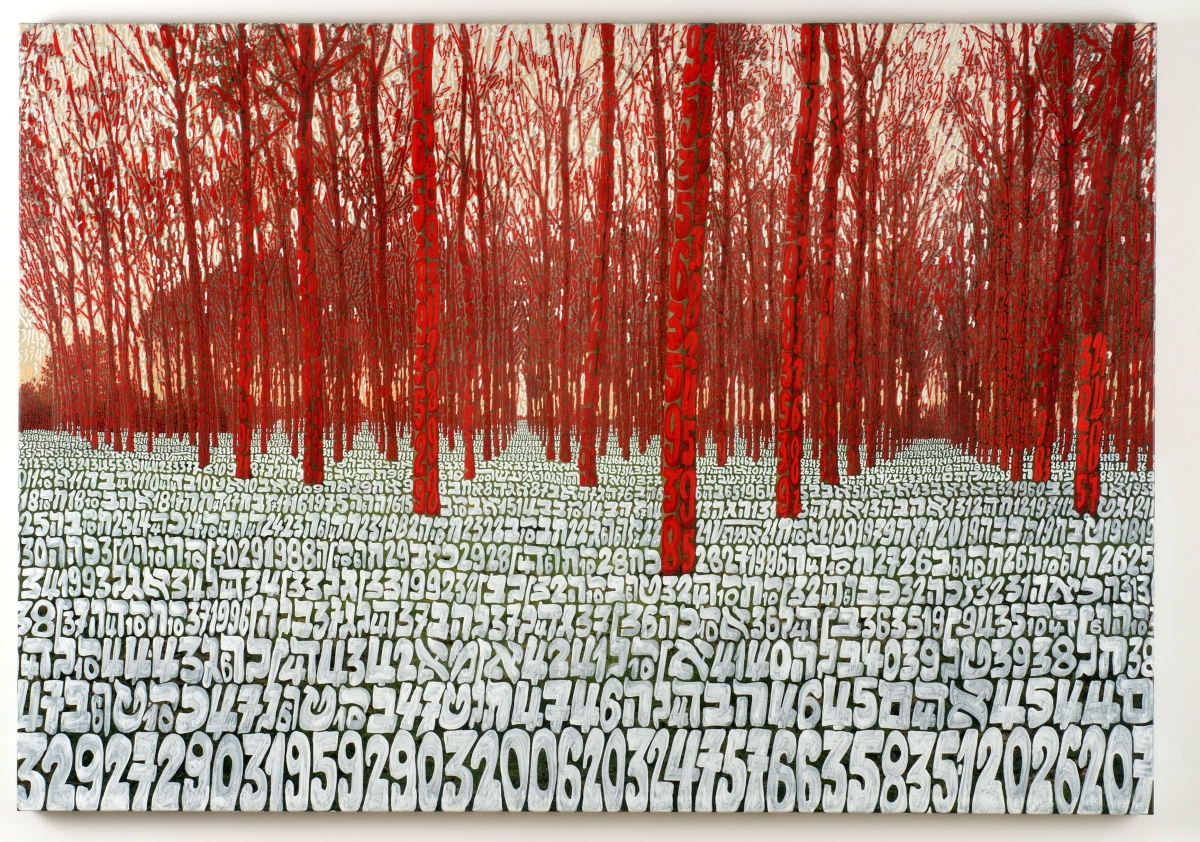

My works are often made up of numbers and Hebrew letters inscribed on images that are produced in a variety of ways: from realistic painting to photography, from emulsified canvas to photomontage using several shots.

However, in recent times, I’ve no longer felt the need to do this. Most of my works are constructed using my previous works, invented from scratch on backgrounds that are simple pencil sketches, or sometimes painted directly onto the canvas without any background.

How would you describe your daily life? Do you have a work routine?

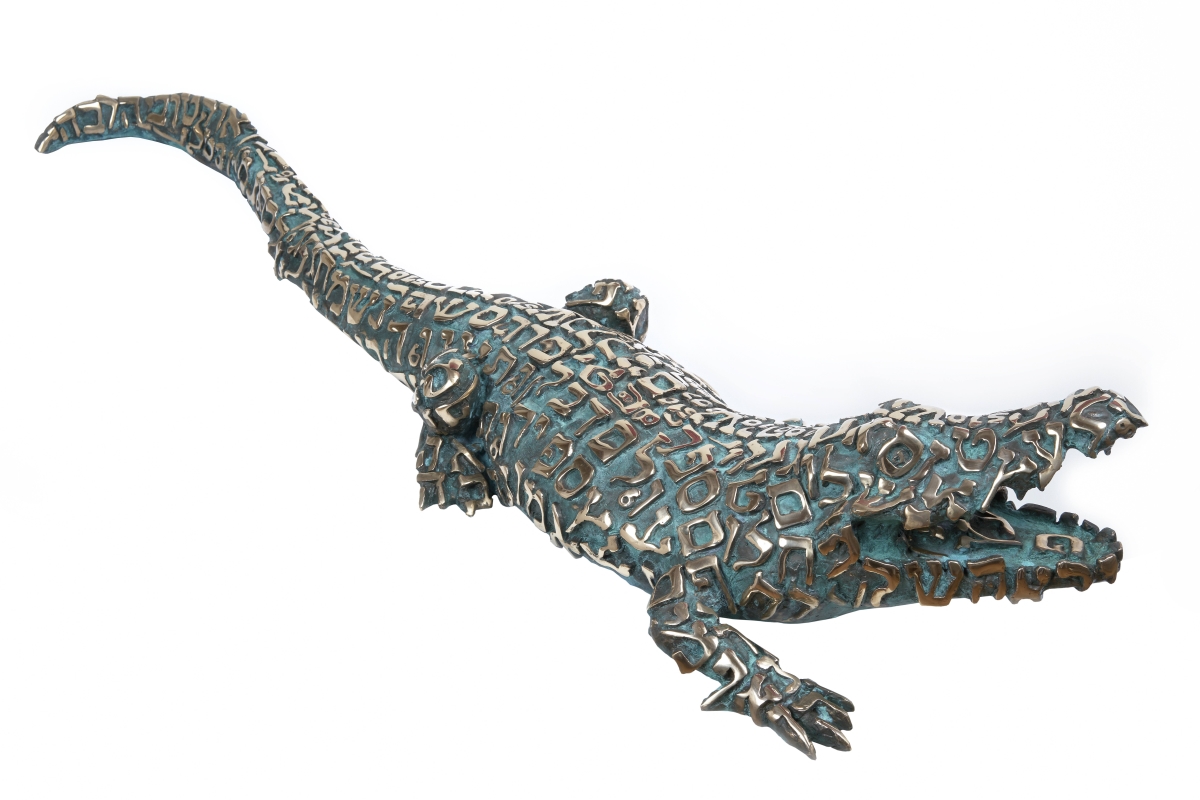

Each day is different from the previous day. After having a good breakfast and feeding our four cats, I sit down at the computer. It’s only when I’ve dealt with all the things I really need to tend to that I can then give my full attention to my artistic practice. I alternate every day; one day I work at the foundry, one day I paint, another day I work on my sublimation satins, or I work with wax to make my bronzes.

Sometimes I go to a glass factory in Murano or do something else. I like to vary what I do because always working on the same piece or using the same technique tires me.

Whereas if I change, it gives me time to think about my work and then go back to it with fresh ideas.

Describe your studio and your work environment. Do you listen to background music while you work or do you prefer silence?

I have a big atelier in Mirano in the province of Venice. It’s part of an outbuilding of a Venetian villa but it is actually older than the villa itself. In the eighteenth century, it was a barn constructed out of an even older house that dated from the fifteenth or sixteenth century. On the two longest sides, the windows look out onto the garden where there are all sorts of trees including both ancient and exotic ones.

Sometimes while working in my studio, I listen to classical music or Italian pop music, or other genres like Israeli music, Yiddish music, or American rock. I also work in silence and listen to the birds in the garden or the cats fighting. Other times, I listen to my wife Luisa’s telephone calls. She’s an art critic and her study is next to my studio. I don’t understand what she’s saying but her voice is soft and sweet, and I like hearing it in the background.

You have exhibited your work in hundreds of galleries and museums over many years. What is the public’s response to your artwork? Do you have any anecdotes to share?

I’ve exhibited in many different countries and continents. My work has been received with great interest, especially by mathematicians, and by the scientific world in general; likewise, of course, by the sphere of Jewish mysticism with its many currents of thought and by those who study the Kabbalah for pleasure or to enrich their own spiritual journey. Psychoanalysts and those who deal with visual perception have also shown an almost morbid kind of interest in my work.

On the other hand, some people have no interest in my work because they don’t like Jewish culture or Jews, in general. Luckily, they’re in the minority. However, there are a lot of people who hate mathematics. At times, numbers can cause anxiety and some people get very worked up about it. Somebody once wrote in the visitor’s comment book: “Damn you, accountant! Go and work in a bank!” Some people think that there’s no place for geometry and math in the humanistic world of art and literature but that’s just prejudice. Artists like Piero della Francesca and Leonardo da Vinci show how the Renaissance actually brought together the worlds of science and humanism.

Tell us about the Concerto d’Arte Contemporanea. How was this organization formed? What accomplishments and success has the institution achieved?

In the mid-1990s, Maria Luisa Trevisan founded the cultural association Concerto d’Arte Contemporanea in Este, Padua. Trevisan is an art historian who later became my wife. The association was created with the idea of bringing together artists, critics, and those working in the art world who share the same conviction that art can set the world right through strong social and ecological commitments, and by aspiring to spirituality and symbolic meaning. In 2004, the association created PaRDeS, a permanent research center for contemporary art, in the grounds and outbuilding of a Venetian villa in Mirano, in the province of Venice, with a second location in my old studio behind the port in Dorsoduro, Venice.

From 2004 to the present, in both Mirano and Venice, we’ve exhibited hundreds of artists—about 30-40 a year—in various thematic exhibitions dealing with science, mathematics, the environment, botany, literature, philosophy, music, Jewish mysticism, women, war, the pandemic, and lockdown. In our most recent exhibition, La Cura, various artists created their own medicinal artwork with a vision for healing and overcoming the serious problems that afflict society today.

Is there an artistic or personal project that you haven’t completed yet?

My work aims to be apotropaic, and to foster positivity for the people who hang it on their walls at home or who just see it in an exhibition. If art is the tip of the arrow of contemporary knowledge and is meant to provide society with spiritual guidance, then I think that my sculptures and pictorial work should serve as a key that is able to open up and profoundly change people’s states of mind, thereby creating individuals capable of living in the future in the most appropriate way.

Perhaps what is still missing in my work is for me to take an openly stronger position against the injustices of our times. So this is what I intend to do: to be more explicit against those who cause pain, such as the Iranian government’s oppression of women, or against people who destroy nature and get away with it, or those who carry out violent acts against neighboring countries in order to steal their wealth and natural resources: not understanding that they just can’t do that today; not understanding that he who has no ethics has no future.

Favorite phrase…

“Carpe diem gefilte fish” “quam minimum credula postero” (trusting in the future as little as possible). By reversing part of the phrase of the Latin poet Horace and juxtaposing it with a classic Ashkenazi dish (stuffed carp), this creates a title that I’ve already used and that involves a play on words in Italian and Latin. The Italian word “carpa”means carp and in Latin “carpe” means “catch or seize.” The idea is to get hold of whatever you can to make the stuffing for the carp or rather, to create incredible works of art.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista