Artist’s Biography

Scott Albrecht was born in 1983 in New Brunswick, NJ, and currently lives in Brooklyn, NY. In 2003, he received a degree in graphic design from the Art Institute of Philadelphia. Perhaps best known for his wood relief pieces and murals, Scott also works in a variety of other mediums including steel, collage, and pen & ink. His work has been published and exhibited both domestically and internationally. Scott has collaborated with a number of clients including Google, Spotify, the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM), Rag & Bone, Vans, PayPal, and Ballantine’s.

Bio source: http://scottalbrecht.com/about

Interview

Artist: Scott Albrecht

By Carol Real

When did you begin using abstract typography?

I studied graphic design, so typography has interested me for a long time. Early on, my work used more traditional type applications. One of the things I noticed when I exhibited that work was that most people were reading vs. looking—consuming a message instead of looking at the work—which can be a much shorter interaction period. Switching to abstraction was a way for me to still work with message and typography, but change the dynamic between a piece and the viewer and encourage more engagement. Because letterforms are abstracted, legibility becomes secondary to form and color. This allows the viewer to consider a piece through a more visual language.

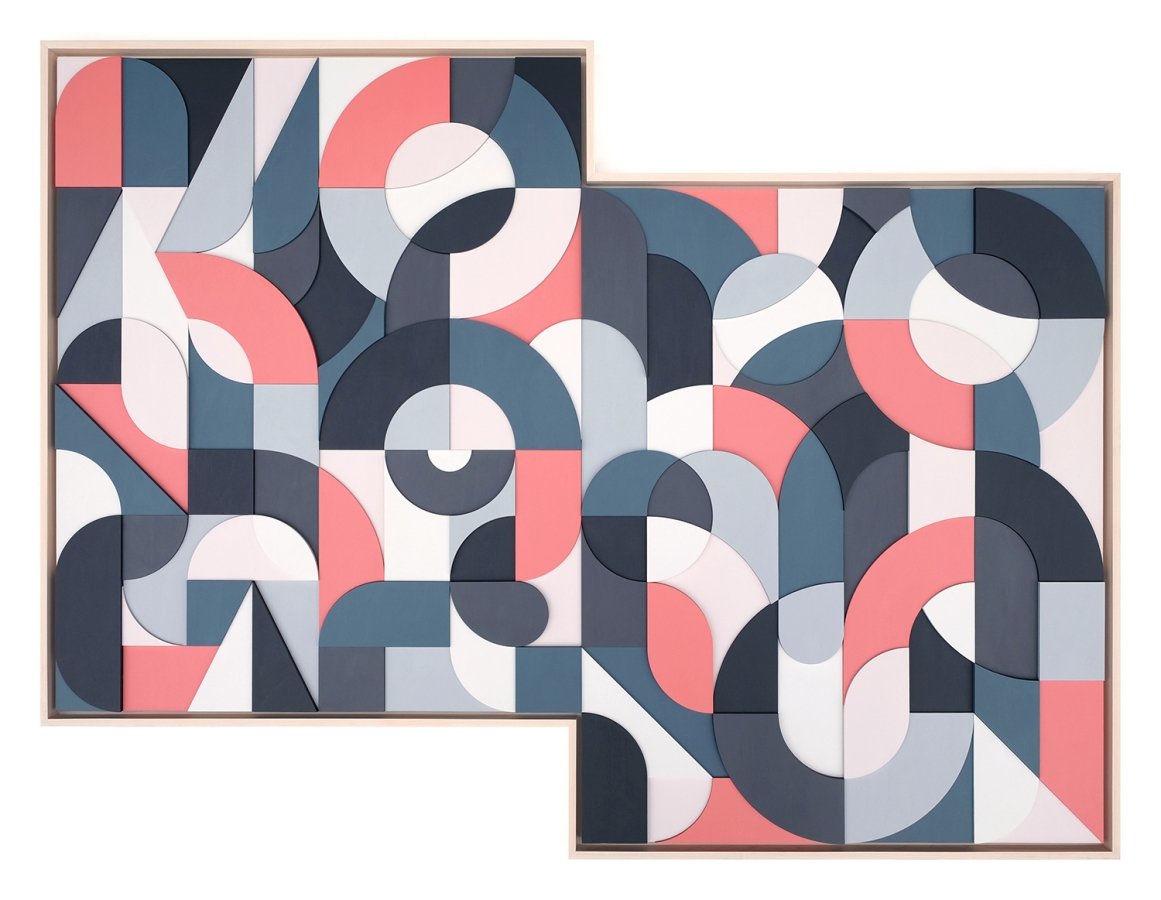

Can you describe your creative process from conception to completion?

Since most pieces are typographic, the process begins with writing. I set aside time at the start of an exhibition or project to write long-form to better understand what I am working towards and excavate some more critical ideas.

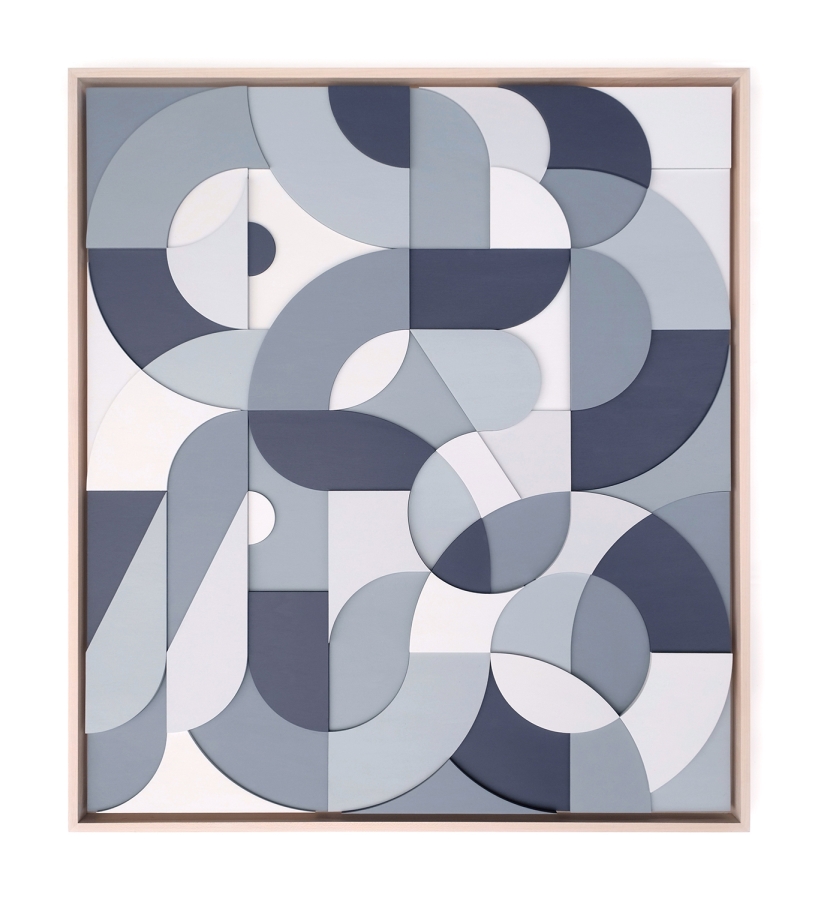

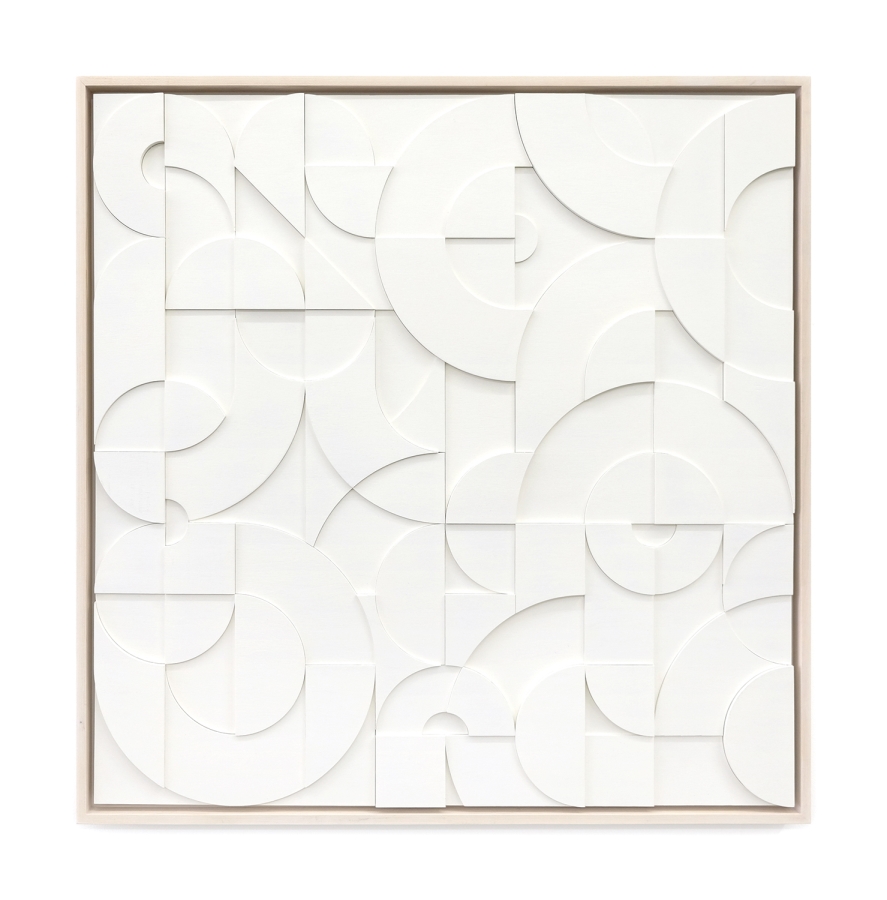

Once I synthesize those ideas, I draw out the work based on the title(s). I move through a couple of stages when sketching that help me map out the character placements and refine the relationships before exploring color.

In most of my woodworks, once the piece is sketched out, the forms are laser-cut. Then, there’s a lengthy process of hand laminating if it’s a relief (to achieve varying depths), sanding, painting, and re-assembling. When complete, most works are the result of dozens, sometimes hundreds of individual pieces coming together to make a larger piece.

Is your distinctive color palette symbolic?

With color, in particular, I look at tones and collective palettes as representing mood. Since my work is abstract, color is the first point of communication with the viewer.

Within the sentiment of a title, there is usually a layered context informing my relationship to that idea. Translating that to a palette means identifying the feeling(s) associated with that idea and playing with all the levers of how those colors feel together—warm and cool, light and dark, levels of saturation, balance, and cadence of tones throughout a piece. In general, I try not to repeat palettes. They may appear similar in some instances, but with all the colors being hand-mixed and with varying palette combinations, I try not to overlap the same specific palette.

I tend to gravitate towards a desaturated spectrum palette versus something less varied or monochromatic, unless the piece calls for it. I like the range of emotions you can get and appreciate the communication of desaturated colors.

What is your typical day like? Do you have a routine?

I do have routines, but I think my days vary depending on what I’m working on or what stage in the process I’m at with a piece or project. I split my practice into different spaces, including studio, exhibition, public work, and collaborations. I try to engage with all of those throughout the year to vary my work and process. Depending on what I’m working on my days can be very different because they all have distinct considerations and approaches.

In a broader sense though, routine-wise, I try to keep regular hours at the studio, usually 10 am until 6:30 pm, and take a walk once a day to get out of my space and break up the day. I think it can come off as formal or regimented. However, I must block out time in the studio and time for myself outside of the studio.

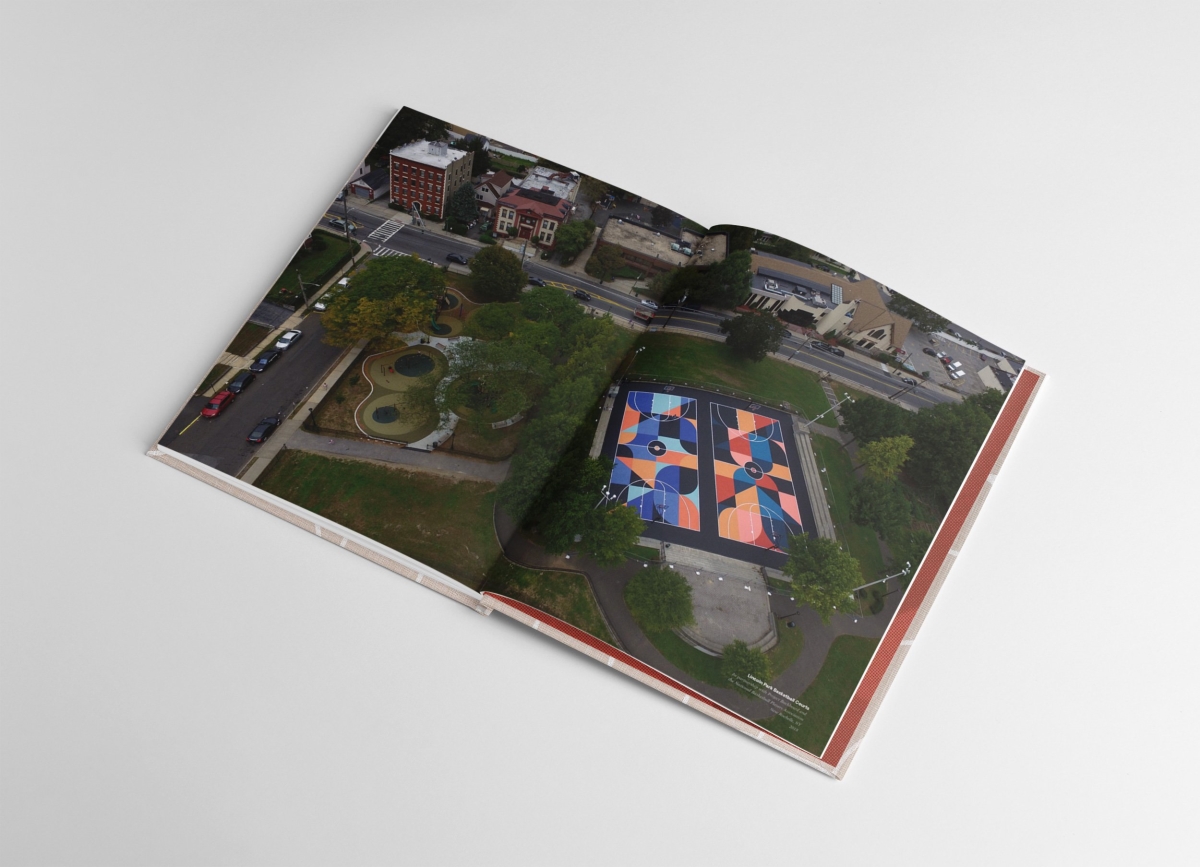

How does public art interfere with people’s lives?

I think interference depends on the viewer. Public art involves a community and becomes a backdrop for everyday experiences. How people receive and engage with a piece depends on the individual and their connection to the space, the community, and what public work could be.

In my approach, I look at public work as being in conversation with that environment. Stylistically, I may be on one side of that conversation with the work being aesthetically similar to a studio piece. However, the sentiment, scale of forms, and colors are different because the audience and environment are different. Since the space is communal, I try to honor that by having an approach that allows for connection and conversation with the work.

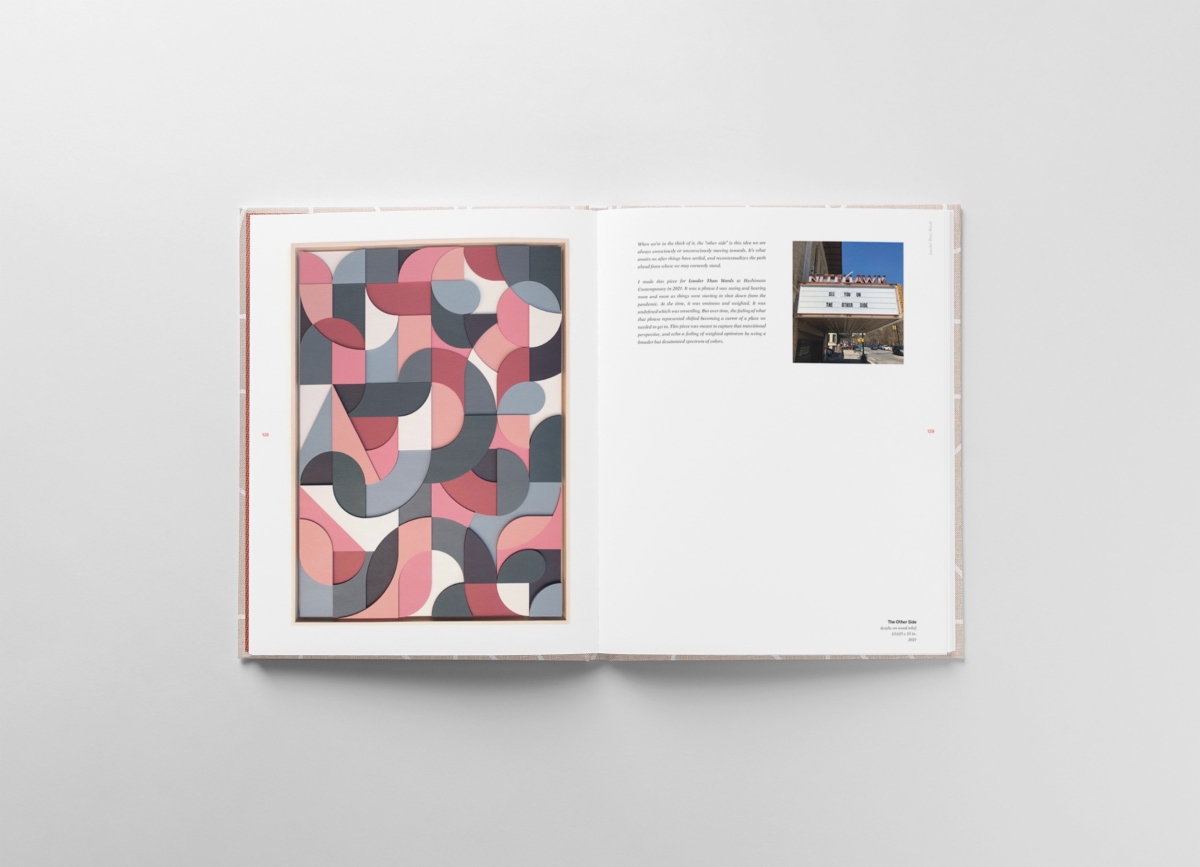

What was the most difficult work to complete? And what work have you enjoyed most so far?

I think my exhibition, Waiting for Our Eyes to Meet, at Hashimoto Contemporary in 2020 was the most challenging. I started planning that exhibition in late 2019. However, things started to shut down because of the pandemic right when I was making the work. At that time, it challenged almost every aspect of my practice. There were looming existential concerns that made me question things on a foundational level. However, on the practical side, it was just too difficult to do anything. The entire world was on a rolling delay. There were massive supply chain issues. Non-essential stores were closed making it difficult to get supplies or work with vendors. My studio had also closed temporarily, so I relocated to an additional studio during the height of the pandemic to continue working. I moved back to my original studio when it reopened two months later before the show opened. In the end, I’m happy with how everything turned out. However, there was so much juggling and pivoting to create the final installation.

As for the work I like the most, I enjoy all I do. However, I get deeper satisfaction when I see viewers engaged. I find public art has fewer barriers for people to freely connect whereas a gallery can feel intimidating to some viewers.

What limitations and challenges did you face while creating these monumental murals?

I’ve gotten pretty adept at estimating my process for spaces, but each mural is different and creates its own set of challenges. I think the biggest limitation is usually time and there’s a range of factors based on the environment that can influence that.

If a mural is outdoors, the schedule depends on the weather. Wall surface and texture can impact paint application. For instance, if a surface is flat you can brush or roll large swaths of color faster and easier. However, if the space has a texture like a gate or slats you will most likely need to approach the space more carefully. Also, the way you reach or access the space can influence things like using a lift. This can be a big benefit over a ladder, which can be pretty limiting if it’s a large wall. I think everything has its own set of problems or challenges, but if you identify them you can plan for them.

If you were not an artist, what other profession would you have chosen?

I worked as a graphic designer and art director for 15 years. I feel pretty fortunate to have experienced that and brought some of this knowledge into my current practice. If I weren’t working as an artist, I would most likely work in that space in some capacity. Then again, if it were a harder pivot, I would be interested in helping or supporting creatives. I don’t know exactly what that would be, but I get a lot of enjoyment from helping people.

What can you tell us about the retrospective book of your artwork? What was the production process?

At the end of 2021, I was burned out. On top of the pandemic intensity, I felt like I hadn’t breathed for two years. I moved between multiple exhibitions and murals, each with its own intensity. And since things were largely closed or distanced at that time, working was my only outlet.

After my exhibition, Louder Than Words, in LA, I needed a break to process things. I took some time off, and when I got back to the studio, I wanted to find an alternative outlet to connect with the work that wasn’t produced. I love books and wanted to make a more in-depth view of the work and process to share with people, so I decided that was a good way to focus.

I took on all aspects of the publication process, including design, layout, writing, collaborating with friends on essays, photos, and editing. I also worked with a printer and handled distribution. It was more work than I had initially anticipated, but I think it was the right project at that time. I usually experience the work individually or in an exhibition environment, which are snapshots of the practice, but publishing a book that was a retrospective of 5 years of work was a way to look at everything more zoomed out and appreciate it through a different lens.

What other places in the world would you like to exhibit your work?

I’m really happy to take it anywhere. At this point, the work has been to more places than I have been able to go so I’d like to go along for the ride 🙂

Favorite phrase…

Be kind.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista

Book link here